Cuddly robots and apps for addiction: how life sciences are tackling social issues

As Alexandre Colle speaks about his “huge passion” in tackling loneliness and social isolation, Maah is wiggling away quite happily on the desk next to him, purring softly. Colle keeps having to pick Maah up and move him backwards so he doesn’t crawl off the table and hurt himself. Maah is really quite endearing and it’s difficult not to be enamoured with him – even in the full knowledge that he is not an animal, but a robot.

Colle is the co-founder of Konpanion, a small robotics company based at the National Robotarium at Heriot-Watt University. While finishing his PhD project on social robotic design, Colle came up with the idea for Maah as a low-maintenance alternative to pet ownership.

“Animals and pets are wonderful. We connect so much to them, we build a bond and trust. They have a role in society as a social and emotional buffer, but some people can’t have pets. I think we could have something with robotics,” Colle says.

Maah is a much simpler design than other social robots. Rather than trying to resemble a human or animal, it is pillow-shaped and made of soft materials. This is to bring a “gentleness” and a “warmth” to it, Colle says, contrasting it with the “metal army of machines” most people think about when they hear the word ‘robot’. Indeed, there are plenty of examples of these types of humanoid machines all around the Robotarium.

But to truly be convincing as an animal, Maah needs to seem like an autonomous creature with its own mind. “The principle of autonomy is very important, and autonomy comes from anthropomorphism,” Colle explains. How to do this is what his PhD research is all about. “What you need is certain behavioural responses, you need to be able to have a believable character. That can come from body language, the expression of emotion, not just semantic skills.”

It can be as simple as ensuring it responds to being stroked, or even having it occasionally act in a seemingly random way, “like he goes and stares out the window, and you don’t know why he’s by the window, but he’s there and then comes back”. All of this helps to build a “very complex emotional attachment” with the robot. This is Konpanion’s mission, to develop something which simulates the companionship of having a pet.

Research has found that social robots could be an effective tool to combat social isolation as a result of this attachment, with a University of Glasgow study finding that over time robots can provide comfort, improve mood, and reduce loneliness. And while Colle accepts Maah would be no replacement for human companionship, he believes there is a place for it – particularly in social care settings for older people.

“A sense of purpose can come from different things. We can be critical of it, we can say ‘why do we need this? Human beings are better’ – I won’t disagree. But that doesn’t solve the fact we’ve got a problem right now which is really impacting people; it’s making people age, it’s detrimental to physical health, it accelerates symptoms of dementia. Loneliness is a real disease.

“Can it be solved by Maah? It would be crazy to claim that, but I think we can give some gentleness, some presence, a connection, some reassurance, and at some point a sense of nurturing where you can care for something and something will care for you back.”

It is about shifting sick care to a wellness paradigm

Konpanion and Maah is just one example of the life sciences sector turning its attention to social issues. While Scotland and the wider UK have enjoyed huge success in the field in recent years, generally this has focused on pharmaceuticals, health tech, and agritech. But with growing recognition of the need to improve public health through prevention and increasing awareness of the social determinants that impact health, the sector is seeing new opportunities for further growth.

At King’s College London, Professor John Strang is trialling a mobile app to support people with drug addictions after they leave prison. While he’s done a great deal of work in Scotland in the past, this next study takes place in England. However, given the high rate of drug deaths north of the border, he expects it will be useful to policymakers here, too.

“Prison release is the time of a horrific concentration of drug overdose deaths,” Strang explains. “In that first week after you come out, your risk of death is 40 times higher.”

This is despite prison being an effective starting point for the treatment journey because drug-taking behaviour is usually interrupted. But there is an apparent lack of continuity beyond the prison gates. “Coming out of prison, you’d think there was an efficient continuity of care – and in fact, it’s pretty disappointing that people who we’re focusing on at the moment with this trial [don’t have that]… Of the people coming out with that planned continuity of care, only 40 per cent of people begin that treatment.

We can think of that as a friendly nudge, prompts that you would hope a brother or sister or partner or friend would give you

“If you take the assumption that by and large you wouldn’t bother to go through the process of starting the treatment and asking for its continuity if you didn’t have some moderate resolve that that’s what you wanted, to have more than half of cases fail shows the baton gets dropped.”

And so the plan is to provide 1,000 prisoners with mobile phones and a three-month contract. An app, made by a Texas-based company, will be installed on some of them (a control group will get the phones but no app) which will make daily contact with reminders of clinic appointments and other useful information. “We can think of that as a friendly nudge, prompts that you would hope a brother or sister or partner or friend would give you. It doesn’t guarantee you get there, maybe it won’t make a difference, but that’s why you do research to find out,” says Strang.

The measure of success will be whether it leads to an increase in the number of people who “successfully get from the prison gate to the beginnings of treatment”. It’s another example of using new technology to tackle a social issue.

Strang has found Scotland a welcome participant in his research over the years and goes on to detail another current project with a Scottish company to create a “wearable device to detect overdose”. His work on overdose prevention in the past ultimately led the Scottish Government to adopt the Take Home Naloxone programme, providing drug users and their families easier access to medication that reverses an opioid overdose. “Scotland very much picked it up, ran with it faster than the rest of the UK did and became the first country in the world to introduce it as national policy. That’s a story that Scotland has written quite a lot about and is quite proud about, and justifiably so,” he says.

Tina Woods, the chief executive of Collider Health, says Scotland has the “perfect environment” for conducting trials as the life sciences sector gets to grips with this pivot to preventing ill health. That’s down to a good-sized population, the structure of health boards, and the willingness of policymakers and government to consider new innovative models.

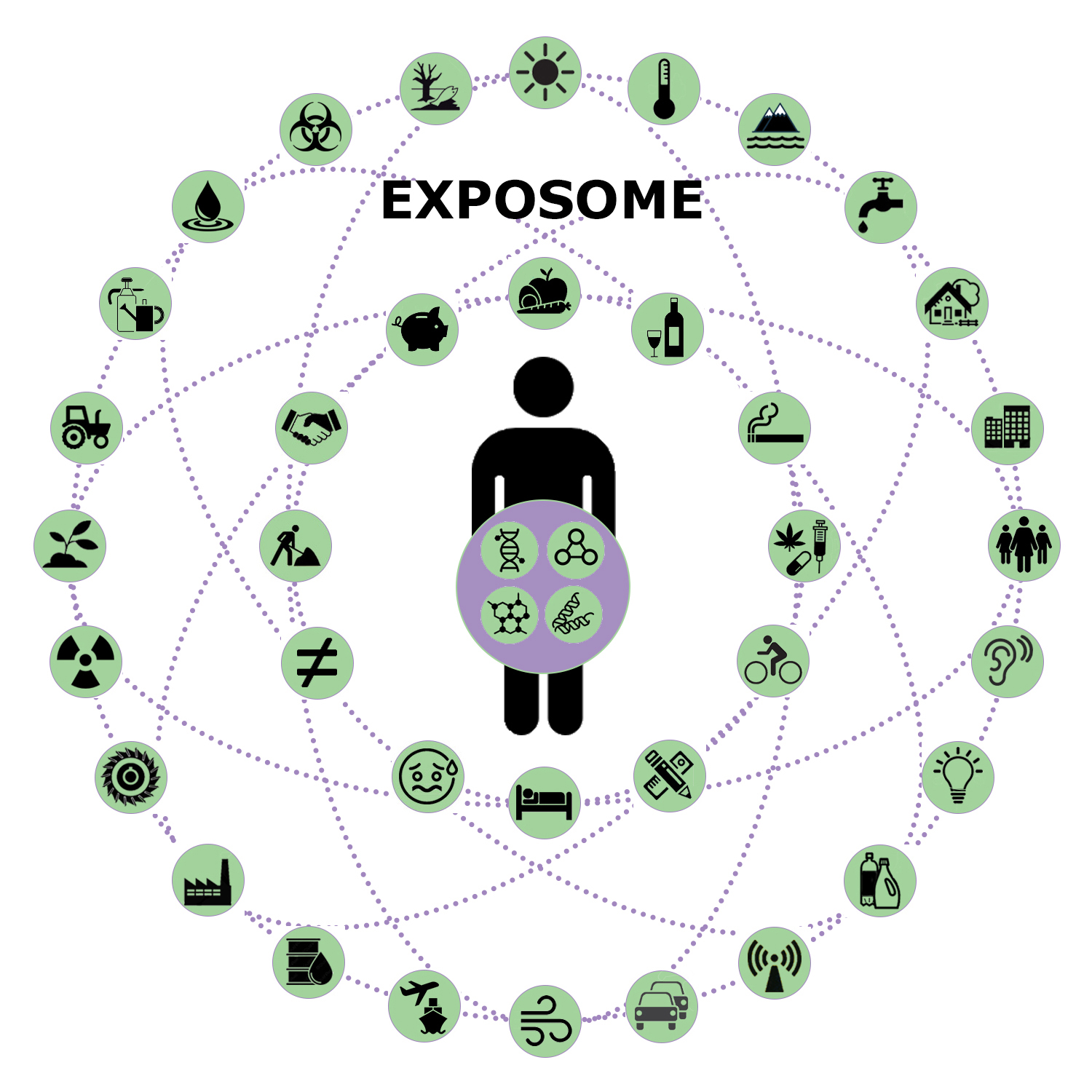

But Woods wants to see much wider changes on what she calls the “new frontier of longevity”. She’s part of the team behind the Human Exposome Project, which plans to map out all external influences on health using communities and cities as “living labs” – collecting data from real people in real-word test beds, rather than a clinical or laboratory setting.

“All my work ties into this idea that we have to understand how the external stresses and environmental risks in our life affects our biology across a lifetime,” she explains. “There’s more and more research that shows how profoundly these external stresses in our life, environmental risks, psycho-social stress, all those sorts of things have a huge and important bearing on our epigenetics, how our genes express themselves or our physiology or how we age.”

It’s somewhat akin to the highly-regarded Human Genome Project, the international study which aimed to map our DNA, but looking externally rather than internally. The Human Exposome Project will allow governments to get new insights on the drivers of poor health, which can help “inform policy and investment decisions so that we stop just thinking about fixing us when we’re sick”.

People are much more willing to look at investing to reap a future benefit

“We’re always going to need great treatments to fix us,” Woods continues. “That goes without saying, and they will become better and better, more personalised. But what I’m saying is it’s about moving upstream into the preventative space, and it is about shifting sick care to a wellness paradigm. We have the technology now, we have growing science, it is about moving upstream.”

And while she’s critical of some parts of the life sciences sector – there are “perverse incentives”, she argues, as firms profit off chronic disease – she also says that “most life scientists worth their salt have already been looking at this space, but what they’re trying to get their head round is the business model, because at the moment that’s the problem”.

Mark Cook, co-chair of the Life Sciences Scotland Industry Leadership Group, accepts that it has been “difficult” to secure funding in the prevention space in the past, but the sector is getting better at selling itself. There’s also much broader recognition that this is an area which needs to be invested in. “I think that the governments and health systems are much more responsive now. We see around the world and here that people are much more willing to look at investing to reap a future benefit,” Cook says.

Indeed, he says its no surprise the life sciences sector is looking to expand in these new areas. “Talking about the cost of healthcare in particular going forward, the way that we feel that we have to go is to go upstream and identify people earlier so that we can intervene earlier… There’s always going to be the need to intervene and fix things, but if we can prevent more, that’s really where the life sciences industry comes into its own.”

And while there are some “bottlenecks” government could help with – such as more “ready-built spinout spaces and laboratory spaces”, as well as improved transport links – Cook says on the whole, both the Scottish and UK governments have been highly involved in growing the sector as it looks towards preventative health and social issues.

“We really feel that we’re working together, not against each other, which I think is absolutely critical because we both want the same thing. Ultimately we want a strong and successful industry and we want a healthy population. It’s always easier when the parties want the same thing.”

And there are huge gains to be made – and indeed have already been made. The sector exceeded its target to generate £8bn for the economy by 2025 and is now in the process of setting a new target – “25 by 35 – that’s £25bn by 2035”, Cook says. Much of that will come from exports. “We are a very big exporter of the things that we do. In the 2021 figures, we turned over £10bn and over £4bn of that was exported. The things that we invent, the world wants.”

Back at the Robotarium with Colle and Maah, he agrees Scotland has a lot going for it. “I think Scotland is very, very advanced and very open to innovation. People want it.” And while for him it’s rewarding enough watching people “smile, hug, embrace” and “go crazy about” Maah, it’s also part of a “social mission” to respond to the next generation of problems – a mission that life science businesses are getting behind.

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe