Truth be told: The dangers of general election deepfakes

Politics and satire go hand in hand, but general election deepfakes created in the name of humour have shone a light on the dangers of misinformation in the digital age

The six weeks since Rishi Sunak announced the general election have almost come and gone. The doors have been knocked, manifestos laid out, and leaders’ debates have been held. It’s a format familiar to all.

Interestingly, some of the new pledges from some of the parties have an odd sense of familiarity to them. For example, following Nigel Farage’s announcement to stand as Reform’s candidate for Clacton, the Conservative Party vowed to cut immigration by creating a new annual cap on visas.

The plan would see the government ask the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) to provide a recommended level for the annual visa cap, which ministers would then consider before putting the proposals to parliament for a vote.

It left many fans of noughties UK TV comedy scratching their heads, as the Tories seemed to be seeking policy inspiration from the political sitcom The Thick of It. Its special episode Rise of the Nutters centres around an undercover investigation into immigration conditions following intense controversy as the prime minister prepares to depart office.

After hearing the Tories’ plan, the creator of the programme, Armando Iannucci, said: “Those asking if The Thick of It is writing this election may want to note that today’s Tory immigration plan – shunt it off to an independent body to decide so that ministers can avoid talking specifics in interviews – is the main plot of 2009’s special The Rise of the Nutters.”

It is likely that instances like this prompted Peter Capaldi, who plays the no-nonsense spin doctor Malcolm Tucker, to say earlier this year he is “not terribly keen” on revisiting the series due to the current state of politics, describing it as “beyond a joke”. Similar comments were made by Iannucci at the 2022 Edinburgh Book Festival when he was asked about a possible return for the programme, and suggested politics is already too satirical now.

Richard Marshall, chief analyst and AI advisor with Texas-based Data Kinetic, says it’s hard to argue that satire doesn’t have a place in politics, and points to examples like Private Eye and Spitting Image, both of which are engrained in British political culture.

However, much of the satire appearing on social media throughout this general election campaign has been made by creators who are not bound by regulations like the powerful and prolific political satirists Brits have watched and read in the last 100 years.

Despite increased usage of social media platforms as sources of information, the public is aware and worried about the potential for misinformation, according to a recent report from the Alan Turing Institute.

Published in May, it found that 85 per cent of people are concerned about the spread of misinformation across social media. It also found that 80 per cent had low or no trust in the UK Government, with almost two-thirds believing it had tried to mislead them.

My concern is what sources of information people can trust. Where are people placing their trust?

Similar results were found regarding mainstream media, with around three-quarters of participants sceptical.

Marshall argues that the public’s willingness to engage with heavily satirised content in the lead-up to the general election has been stoked by instances of “lying” by politicians and a “lack of trust” in information sources.

“In the UK, this certainly started with the [Brexit] Leave campaign, and it’s interesting to look at the fact that the Leave campaign was allowed to get away with horrific lying and disinformation,” he says. “And nothing has been done about that. People like [former prime minister] Boris Johnson would say whatever they felt would get the greatest coverage and make the biggest impact.

“My concern is what sources of information people can trust. Where are people placing their trust? I do think that the end result is more echo chambers.”

He uses the example of comedian Janey Godley’s voiceovers of Nicola Sturgeon’s pandemic updates to show how satire can be used to communicate to a wider audience.

“Satirical messaging can work in a positive direction so long as it’s being done in a funny way,” he says. “It also actually takes a lot of the seriousness out of it, which can be helpful because it enables people to see things from a slightly different way.

“If we go back to Spitting Image and Victorian cartoons, none of that was about destabilising. It was about trying to get a message over, whereas the destabilising content [on social media] is just making trouble. And there are lots of people out there who are able to monetise it or use it for political gain.”

.jpg) Boris Johnson's Leave campaign bus | Alamy

Boris Johnson's Leave campaign bus | Alamy

A report from The Guardian last month tracked the usage of six volunteers’ phones over three days to understand what news they were consuming during the lead-up to the general election. The findings, from the perspective of mainstream media, are concerning.

There was a clear generational divide. Three participants under 40 rarely, if ever, engaged with mainstream news outlets and instead seem to have formed their views from social media platforms such as TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook, while older voters were found to still seek out mainstream broadcasters such as ITV and the BBC to stay aware of the news agenda.

It was clear that while the younger voters do have some trust in outlets like the BBC, they do not have the same connection to mainstream media outlets. Instead of showing interest in the broader news agenda, the key issues they deemed directly relevant to their lives were the war in Gaza, gender issues and housing.

It concluded with three takeaways: voters are seeing less political content on their social media feeds; traditional news outlets are less prominent in their lives; and influencers have an ever-greater role in shaping political opinions.

Often, online political content creators look to use satire to improve their engagement. However, in a heavily polarised world the use of humour can easily become a source of chaos and disruption. And, with technology only a few keystrokes away, anyone could take content too far.

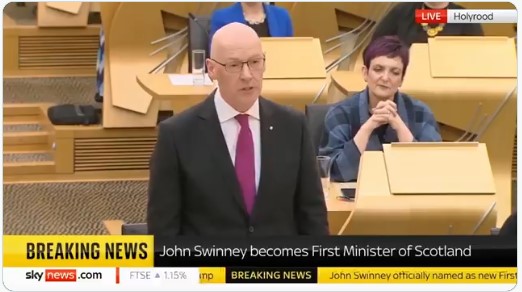

A Glasgow-born X (formerly Twitter) user who lives in the United States creates satirical deepfake videos to poke fun at politicians. In one of these AI-generated clips, First Minister John Swinney is made to suggest that after the general election, the SNP plans “to do whatever we want”. In a matter of days, the clip went viral with tens of thousands of views – just under two weeks before Scots head to the polls.

A screenshot from the deepfake video of John Swinney on Sky News | X

Speaking to Holyrood, the deepfake creator behind the video says he does it to “take the mickey out of politicians”. “It’s very easy to mock them,” he adds. He chooses political figures because they are the “easiest” to target “given the amount of rubbish that they come out with”.

On a Zoom call, with the camera turned off and using a fake name, he walks through his process of creating the AI-generated content. Self-taught by watching a YouTube video, he uses a programme called ElevenLabs, an AI-voice generator, to create his clips. Since its launch in January 2023, ElevenLabs users have created more than 100 years-worth of audio material.

He uploads the audio file, types in what he wants the politician to say and within 30 seconds, the platform creates the fake audio. The man then uses software that manipulates the lips of the original video to match the new audio. And in just 10 minutes, he has created a deepfake that could reach tens of thousands of people.

Regulations will not happen until there’s a massive disaster. There’ll be a cyber security breach, and it’ll probably happen in America. It’ll be a Grenfell Tower version online.

However, he tells Holyrood, it is not his intention to influence voters. “I wouldn’t stop doing it, but I would look at the video that would maybe cause [misinformation], and think, why?,” he says. “What have I done to make it like that? Because that’s not my intention. My intention is just to have fun and take the mickey. So if I made a video, and it came across with people believing it, then I’d know I had done something wrong.”

However, one of his videos does appear to have been taken seriously by some social media users.

A clip of Green MSP Maggie Chapman watermarked with the Scottish Parliament TV tag and the Scottish Sun logo has gathered 34,000 views and has more than 150 reposts. The audio in the video says: “We would like to start demolishing all Scottish roads. Every road is a symbol of white, heterosexual supremacy.”

The creator insists it is “pretty obvious” his videos are manipulated, but comments suggest otherwise. One reads: “She is beyond nuts.” Another person wrote: “Listen to this lunatic who worked with the SNP, Scottish Greens are crazy people.”

It appears the increasing sophistication and accuracy have made it more difficult for people to determine what is real. A study from 2021 by the University of Amsterdam appears to corroborate this. It found that people cannot reliably spot deepfakes and reported that viewers overestimated their detection abilities. In short, participants demonstrated high levels of detection confidence but scored much lower when asked to accurately identify deepfakes.

Lucy Bately, owner of Traction Industries, an organisation that helps integrate AI and future tech into businesses, paints a worrying picture of a group of people who could be affected particularly badly by deepfakes.

“I’ve got an 11-year-old daughter and I keep showing her AI-generated images and it’s amazing, she’s unbothered because she’s grown up with TikTok and all the AI filters, so she can’t tell the difference between what’s AI and what’s not,” she says. “It’s just normal.

“A lot of people aren’t even computer literate or IT literate. I’ve just had a conversation with a guy this morning who knew nothing about AI. There’s a massive percentage of the population that aren’t even kind of aware of it.”

The potential for deepfakes to influence tight elections is not unprecedented. Last year, just two days before the Slovakian election, a deepfake of the liberal candidate Michal Šimečka went viral. In the clip he appeared to discuss ways in which he might rig the vote. Šimečka went on to lose the close race to the candidate from the pro-Russian Smer-SD party. Although it is unclear how much the clip influenced the election result, it was watched by thousands of people and dominated public discourse ahead of the general election.

Michal Šimečka, leader of Progressive Slovakia | Alamy

Michal Šimečka, leader of Progressive Slovakia | Alamy

Bately is clear that an effective global approach to regulation around this type of AI-generated content is further away than many hope.

“The whole global regulation of AI is an absolute mess at the moment,” she says. “America is doing one thing, the EU is being really strict about it, and the UK really loose. So unless there’s a global agreement there will be no progress.”

She adds: “From my point of view, regulations will not happen until there’s a massive disaster. There’ll be a cybersecurity breach, and it’ll probably happen in America. It’ll be a Grenfell Tower version online, something massive will happen, and then they’ll clamp down and regulate it all.”

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe