The State of Independence: The long shadow of Scotland's 2014 referendum

Standing at a lectern in London on the day after the Scottish independence referendum, then-prime minister David Cameron declared that “the debate has been settled”.

“We have heard the settled will of the Scottish people,” he said, adding that the matter had been put to bed for a generation, “perhaps for a lifetime”. “There can be no disputes,” Cameron asserted, “no re-runs.”

Cameron had gambled correctly on a No vote being returned on 18 September 2014. But he was wrong about the debate being settled. For 10 years it has loomed over all other conversations about politics and policy. After Brexit, Covid, the death of the Queen and the cost-of-living crisis, through five prime ministers and three first ministers, the discussion has continued.

When pockets of intense argument have ignited, variously, over ferries, wars and bottle recycling, gender recognition reforms, public spending and exam results, the constitution has been invoked by MSPs keen to talk about what ‘could’ or ‘would’ happen – good and bad – under a different settlement. Indeed, the words ‘independence’, ‘referendum’ and ‘indyref’ have been uttered more than 3,100 times in the Scottish Parliament’s debating chamber alone since 2014.

Recent polling puts support for independence at or close to 50 per cent, when ‘don’t knows’ are excluded – higher than the 45 per cent returned a decade ago. And though former first minister Humza Yousaf described Scottish sovereignty as “frustratingly close” in his resignation speech in May, there is now an open admission within the SNP that this is not the case. “Support for independence is stronger today than it was in 2014,” Yousaf’s successor John Swinney told Newsnight. “That’s what the opinion polling shows; consistently stronger, and it’s about 50-50 just now. But that’s not enough.

“I don’t accept that independence is frustratingly close.”

Proponents on both sides argue that theirs is the only compelling case on the constitution. On the Yes side, Scotland is held back economically and socially by a UK Government that does not serve the interests of the Scottish people; on the No side, the UK Government is protecting pensions and the economy from the nosedive that would follow secession and preserving the country’s place on the world stage.

But commentators say those arguments are little changed over a decade, despite all the talking. And, on the question of how Scotland could achieve independence, should its people want it to, there are even fewer answers. Prime Minister Keir Starmer has said he will not agree to another referendum and the Supreme Court, in a judgment forced by Nicola Sturgeon, has said the Scottish Parliament has no legal power to hold one without Westminster’s consent.

And so, with neither side willing to give ground, and with public opinion little changed, we are in a prolonged period of stalemate.

Former Labour adviser Paul Sinclair, who was instrumental to the pro-union Better Together campaign, says he saw that coming. “One of my frustrations was the day after the referendum talking to colleagues from Better Together and saying, ‘how do we keep this going?’, and them saying, ‘but we’ve won’,” says Sinclair, who worked for both Gordon Brown and Johann Lamont.

“Fifty-five per cent to 45 per cent is a reasonable margin but I’d have wanted it to be in the 60s, that would have settled it. So no, it wasn’t settled. What I think is a real pity is on both sides the argument hasn’t moved on. There’s no new argument to leave the UK, no vision, and the pro-union argument is still negative.”

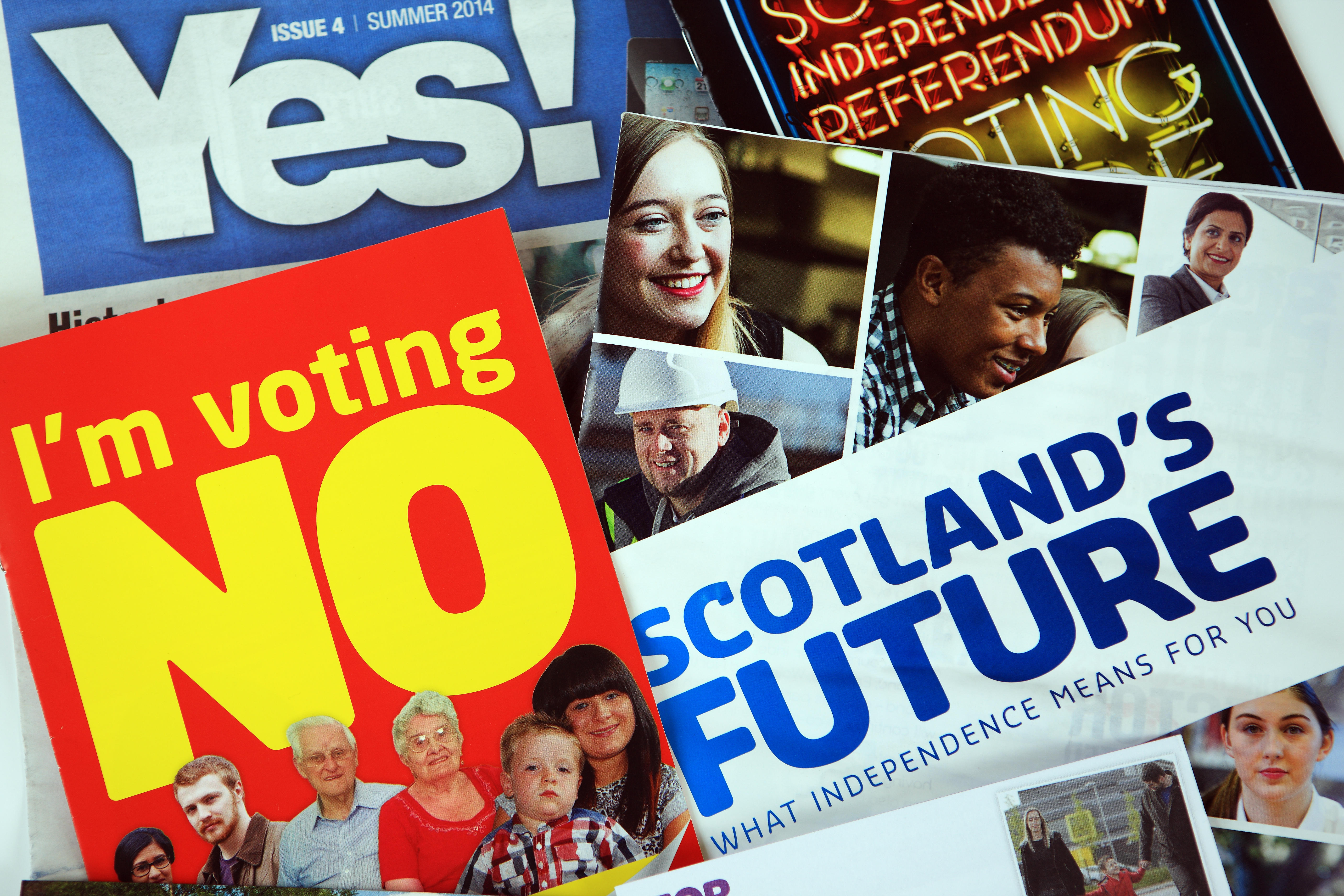

After a two-year run-in, the referendum had ignited the Scottish electorate like no other contest. The long campaign to voting day had started two years prior and the Scottish Government’s 650-page white paper, Scotland’s Future, was downloaded 20,000 times on its first day alone. Voter turnout reached an extraordinary 84.6 per cent, a level unseen in the UK since the post-war period, when 83.9 per cent was recorded in 1951.

Residents of Inverclyde were split 50.1 per cent to 49.9 per cent. At 67.2 per cent, Orkney showed the strongest support for the union, followed by the Scottish Borders and Dumfries and Galloway, while ‘Yes city’ Dundee recorded the highest support for independence at 57.4 per cent. West Dunbartonshire and Glasgow followed.

David Cameron celebrated, pledging to strengthen the union and announcing the introduction of ‘English votes for English laws’. Under ‘The Vow’, as advertised on the front of the Daily Record, the powers of Scotland’s parliament would now be beefed up. A defeated Alex Salmond stood down as first minister and SNP leader, passing the torch to Nicola Sturgeon.

The referendum result has come to represent the greatest opportunity lost in modern Scottish history

Looking back, Salmond – who now heads the Alba Party – feels the “stronger, more politically aware” Scotland which emerged from indyref has been let down. “That great potential for good and hope among the people has been largely dissipated in the desultory decade which has followed with constant pressure on the living standards of families, the monumental economic self-harm of Brexit and the extraordinary and unprecedented governmental maladministration north and south of the border,” he says.

“The referendum result has come to represent the greatest opportunity lost in modern Scottish history.”

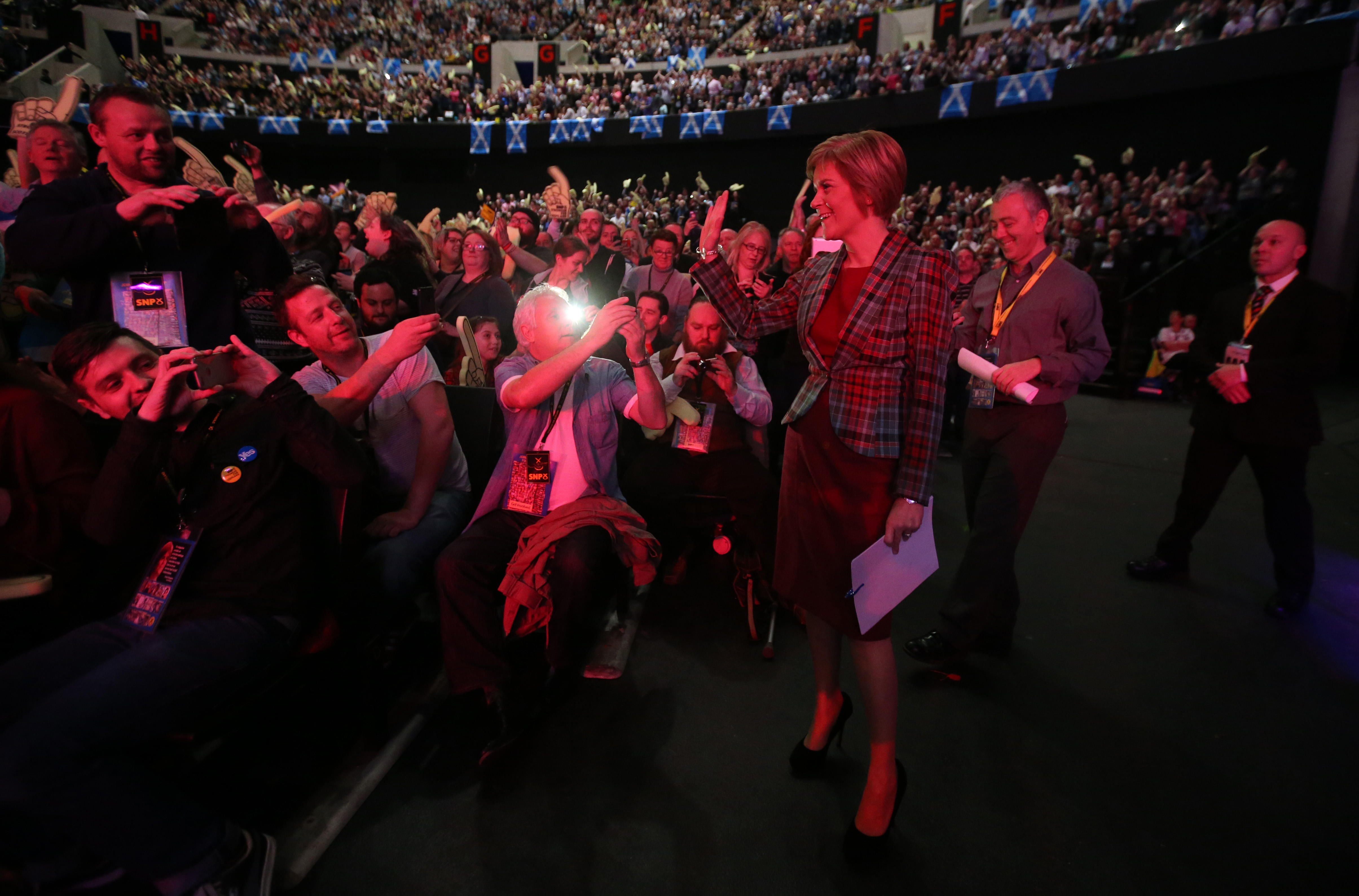

Along with Cameron, who could boast that he would go down as the PM who kept the UK intact, Sturgeon was arguably the individual who benefited most from the indyref result, becoming not only the first-ever female first minister but a political figurehead capable of filling Glasgow’s Hydro concert hall, and one who caught the attention of the world’s media.

Nicola Sturgeon greets supporters at the Hydro | Alamy

Under Sturgeon, SNP membership would grow to 125,691 in 2019, with the party winning a record 56 Westminster seats, demolishing Labour and topping the Scottish Parliament polls for a third and fourth time. It was the former solicitor who would form the first ever pro-independence government of co-operation, striking the Bute House Agreement with the Scottish Greens, and it was to her that indy supporters would look for a way forward. When the UK delivered a Leave majority in the Brexit referendum of 2016 despite Scotland voting to Remain, it was Sturgeon who declared that, in the face of what she called a “material change in circumstances”, a second indyref was now “on the table”.

John Swinney, who stood by as Sturgeon’s deputy in 2016, has now said he was “nervous” of the strategy, asking his boss “was she sure that she wanted to say so firmly that she was opening up a dialogue” on the matter. “I was still concerned,” he told a BBC documentary, “by how we were able to motivate people in Scotland when we had just had one [referendum] in 2014.”

A second run of the vote failed to materialise and Sturgeon issued a surprise ‘hail Mary’ in June 2022, when she announced she would bring forward a bill for a consultative independence referendum. The matter had been referred to the UK Supreme Court already to determine its competency, she told MSPs, even going so far as to name 19 October 2023 as her preferred date for the vote and announcing that she’d turn the general election into a “de facto” referendum if the law was not on her government’s side. “Either way,” insisted Sturgeon, “the people of Scotland will have their say.”

I don't care how you voted in the past

It took just five months for the court to find against the Scottish Government, and Sturgeon resigned three months after that. The SNP entered a maelstrom period in which policies and personalities clashed and senior figures wondered how to make the ‘de facto’ plan work, or even how to articulate it. Membership has fallen to around half of its peak and a complaint over donations to an indyref2 fighting fund has led to Sturgeon’s husband, former SNP chief executive Peter Murrell, being charged with embezzlement. Operation Branchform remains live and police have passed papers on Sturgeon to prosecutors for guidance.

Then, in July, the SNP’s Westminster front shrank from 37 to nine MPs in a general election that saw its vote share dwindle to second place behind an avowedly pro-union Labour. Anas Sarwar – the fifth person to head Scottish Labour in the 10 years since the independence referendum – said his party would “reset devolution” after appealing to former Yes voters to join him to “deliver change” and remove the Conservatives from office. The call was part of a campaign that saw Scottish Labour use the same “Scotland’s Future” wording that had once been used for Salmond and Sturgeon’s pro-independence message. “I don’t care how you voted in the past; I don’t care how you voted in either referendum,” Sarwar said, vowing that through his party, Scots would get a seat at the UK Government table.

According to polling presented to delegates at the SNP’s recent conference, as many as 250,000 voters made the switch. Former local government minister Marco Biagi said that, though there was evidence of some tactical voting, many had simply determined that the SNP was now “a mess”.

Stephen Flynn addresses the SNP conference | Alamy

Stephen Flynn, the SNP leader at Westminster, said Yes supporters had been told too often that “this will be it, this will be it, this will be it”, suffering repeated defeats that had worn away conviction. And he called on his party to “reflect very carefully on language and rhetoric” if it is to win unionists over to its cause.

For Dr Tom Montgomery of the University of Stirling, that’s not all that’s gone wrong for the SNP. Montgomery, an expert in organisations, has been researching the referendum and indy movement “to better understand what 2014 looks like as a political moment”. There was a sense that “the SNP could govern in Scotland for decades” after its 2015 election landslide, he says. And he says Sturgeon’s Hydro sell-out was the moment when the SNP should have been undertaking the strategic planning that could have advanced independence. “Very few people within the SNP leadership stopped at that point and asked what went wrong because at that point it must have felt like a victory,” he says, “but it wasn’t; it was a defeat.

“After the referendum there was that initial period of huge numbers of people joining the SNP. You had hundreds of people turning up to some branch meetings. It’s a huge challenge for any organisation.

There was a real sense that this was a movement putting aside its differences. The same can't be said now

“Examining where strategy has gone wrong hasn’t been common practice in the SNP because it didn’t need to. There’s a growing realisation with comments from some former MPs that things can’t really continue the way they have been.”

Montgomery, who at the time of writing is preparing to publish research on the matter, says the Yes movement has become “more fragmented” at the same time as the SNP’s “agenda-setting ability as a government has declined”.

While bodies like the Radical Independence Campaign, Scottish Greens and the Scottish Socialist Party would hold varying positions from the SNP on the economy, climate and equalities in 2014, “there was a real sense that this was a movement putting aside its differences”, Montgomery argues, but “the same can’t be said now,” with the SNP refusing to work with Salmond’s Alba and the Greens furious over the promotion of Kate Forbes to deputy first minister due to her admission that she would not have voted for equal marriage had she been an MSP when the legislation came through. As for collaboration between Alba and the Greens, their divergence over the heated issue of gender recognition reforms makes that far from likely – putting big question marks over the cross-party, cross-body convention the SNP now aims to assemble.

Russell Findlay wants the Scottish Conservatives to refocus away from the constitution | Alamy

It was announced earlier this month by deputy leader Keith Brown, who said it will “unite with every willing element of civic Scotland committed to the principle of self-determination”. A similar push, involving trade unions, faith leaders and more, helped build momentum for devolution in the 1990s and Brown hopes the same can be achieved now. However, detail on how the convention will work is as yet unknown.

While Yousaf hoped the creation of a Minister for Independence would advance the agenda, the position that was held by Jamie Hepburn has now been scrapped following 14 months of criticism from the Conservatives’ Douglas Ross and others about the use of civil service time and public money on a series of position papers which failed to spark the national conversation that had been hoped for, but which did add to the fractiousness between Downing Street and Bute House.

All of that is perhaps power to the pro-union camp’s elbow, and in his pitch for the Scottish Conservative leadership Russell Findlay MSP has argued that it is time for his party to stop “predominantly battling against independence” and instead lead “a patriotic conservative movement that stands for aspiration and ambition”.

Over the past decade, the referendum result has ensured that more money has been available to spend on vital public services

While Better Together is no longer a campaigning force, Scotland in Union – until recently headed by the now newly elected Labour MP Pamela Nash – continues to advocate against separatism. In polling carried out for the organisation to mark a decade since the referendum, just seven per cent of those asked named independence as one of the most important issues that the Scottish Government should prioritise. “Over the past decade, the referendum result has ensured that more money has been available to spend on vital public services like health and education, and Scottish businesses and workers have benefited from the economic ties with the rest of the UK, which is by far our biggest trade market,” said Scotland in Union founder Alastair Cameron, arguing that time spent on the constitution has “detracted from the important job of government” in Scotland.

The relationship between the UK and Scottish governments has, for much of the past decade, been ill-tempered at best. Ministers on both sides have volleyed criticisms in public and parliament, each accusing the other of letting the public down, failing to compromise and following a narrow political agenda that puts party first. Things got so bad that UK ministers threatened to axe Foreign Office support for the Scottish Government’s overseas engagement to stop independence being discussed with representatives of other countries.

If the mood between the governments has soured, the same is true of the public’s mood, which has changed as the economic outlook has toughened. While the 2014 referendum took place at the back of Glasgow’s joyous Commonwealth Games, which saw investment poured into world-class sporting facilities, new housing and improved infrastructure, 2024 finds us with a Scottish Government that is rapidly cutting back on all but the most essential spending.

High street prices and living costs have increased along with inflationary pressures | Alamy

Finance secretary Shona Robison has put forward cuts to public services worth £500m to balance the Scottish budget this financial year. More than £115m of that will come from health and social care, including mental health services, with around £23m taken from both the transport and net zero and energy portfolios. The finances are so straitened that £460m of ScotWind revenue will be spent now on services – not taking the country to net zero, as was previously planned.

The cuts follow dire warnings from the UK Government over a £22bn black hole inherited from the former Conservative administration. It’s the rationale behind the end of universal entitlement to winter fuel payments, which will now be restricted to those in receipt of pension credit both north and south of the border. “We’re going to have to be unpopular — and tough decisions are tough decisions,” Starmer has said of his government. And though Robison has blamed Westminster decision-making for the position ministers in Edinburgh are now in, the Scottish Fiscal Commission has said her government’s own choices on public sector pay deals, council tax and social security reforms have contributed to “much of the pressure” it now faces.

While inflation has reduced since hitting 11.1 per cent in autumn 2022, the public – and public services – continue to grapple with costs far higher than those seen a decade ago. Food bank network The Trussell Trust gave emergency supply packs to 71,428 people in Scotland over 2013-14. Last year, more than 262,400 such parcels were distributed.

We need to continue to have hope

In Dundee, in which one third of children live in relative poverty, food banks and other grassroots aid organisations supplying clothing and support to households flourished after the independence referendum, according to local councillor Lynne Short. Her Maryfield ward has one of the highest rates of deprivation in the city and the SNP politician looks back on 2014 as “a time when anything was possible”. “The world has changed so much since 2014; us as individuals, we’ve changed so much,” she says.

Like many elected members across Scotland, Short cites the referendum as the period which convinced her to become more involved in politics. “If everybody else had done what Dundee had done, we’d have been fine,” she says of the outcome of the referendum, and she thinks many locals were “brought along” with the wave of Yes support “because of the enthusiasm” in the air. “Since then, everything has become about the constitutional question and I think that’s maybe stood in the way” of progress in some policy areas, she says. Still, she sums up the indyref period “in one word: hope”. “We need to continue to have hope,” she says.

But for Professor Nicola McEwen, director of the Centre for Public Policy at Glasgow University, the past year “has felt like the end of that process that started and led to the 2014 referendum”.

Campaign material from 2014 | Alamy

“There is a soft support there” for independence, she told a fringe event at the recent SNP conference, but not the solid backing the party would need to push that cause forward. At the same event, ex-Scottish Government adviser Stephen Noon argued against interpreting demand for independence as a linear movement, claiming instead that this drive is “probably at the beginning of a new wave forward”.

“There was the move to the ’79 referendum, which was lost, then a bit of retrenchment,” he said. “Then there was the move to the ’97 referendum, which was won, then a bit of retrenchment. Then the move which took us to the independence referendum and beyond and we are probably now… at the end of that wave.

“The challenge for a party like the SNP is to be ready to ride the wave, no matter what it looks like or where it comes from.”

People who think... the issue is dead are wrong

If he’s right, that brings a challenge too for Labour, the Conservatives, the Lib Dems and other pro-union bodies. Ex-Better Together campaigner Sinclair says his former colleagues should be alive to that possibility, regardless of the changes in public feeling, finances and party rankings.

“The mood of 2014 was two sharp contrasts – the Yes supporters believing we were on the cusp of a new age and a new country, and those of us on the other side fearing we were going to damage Scotland enormously,” he recalls. “It was very vibrant, there was passion on both sides. Now I think with all the country has gone through, from Covid to cost-of-living to wars, the constitutional issue has gone cold. But these people who think that means the issue is dead are wrong.

“The electorate has never been so volatile, in my experience. People forget that in February-March 2011 Iain Gray and the Labour Party were ahead in the polls. If you’d suggested then we’d be voting on independence in just three years’ time you’d have been laughed out of court, but we were. That was then, when things were a bit more stable. The idea that one election and some opinion polls mean it’s finished is wrong.

“The electorate has become even more sophisticated. They’re saying the SNP’s record as a governing party is rubbish; that doesn’t mean they’ve changed their constitutional views.”

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe