Solicitor General Ruth Charteris: 'I believe in justice'

Ruth Charteris admits her work sometimes keeps her awake at night.

As Scotland’s Solicitor General, Charteris has one of the most senior legal posts in the country. She came to the role in 2021 after years spent at the Bar. And over those years, she handled cases she admits can affect a person’s impression of humanity. “You are dealing with such horrible cases, your view of people can easily become skewed,” she said. She tries “not to be cynical, not be jaundiced, and to realise that, actually, the vast majority of people out there are not doing these awful things we’re seeing in the awful cases that we do”.

But there are times when the details and victims of some cases do come back to her. “One was a terrible child abuse case,” she said. “I won’t go into the detail, but it involved a certain football club, so whenever I see the badge of that football club it brings it back.

“It’s life, and it’s real,” she goes on. “You know, I can’t complain about ‘poor me, I had my sleep interrupted because I remember that awful case’. I wasn’t the person that it happened to, so if all that happens to me is that I remember that wee boy, then that’s not a bad thing.”

Charteris, who deputises for Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain, is one of a team of women now holding key positions in our legal system, and who are now part of efforts to examine imbalances in that system, particularly those affecting women. As well as Charteris and Bain, the role of justice secretary is held by Angela Constance, with Catherine Smith recently appointed as Advocate General for Scotland.

[with] women in prison there’s a very complex relationship with abuse

The all-female team is a first for our legal system and, speaking to Holyrood editor Mandy Rhodes at the International Law Enforcement in a Digital Age summit in Glasgow – hosted by Holyrood to correspond with the INTERPOL General Assembly – Charteris said that the system must work for everyone.

And that means understanding more about the drivers of offending, as well as seeking reforms to the courts to bring about greater access to and experience of justice.

“A couple of years ago I was involved in a women’s justice initiative with representatives from justice from all over Scotland – prisons, police, justice, the prosecution service,” Charteris said, “and one part of our report dealt with women offenders and women in prison, and it was an absolutely fascinating case study.

“I take my hat off to the women who work in prisons and the amazing work that they do, and the sheer compassion they do it with.

“What we discovered was that [with] women in prison there’s a very complex relationship with abuse. There’s also a real mental health issue going on there and evidence of head injuries in an astonishing number of women inmates. It’s a complex picture that impacts on families and one of the areas that really needs looked at is alternatives to incarceration.

“As a prosecutor in the High Court,” she went on, “I always found it very difficult to look at the accused. If it was a woman, I found that even more difficult.

“I’m not excusing what would have been done; I’m conscious of the tragedies, the probably manageable tragedies, that were in her story.”

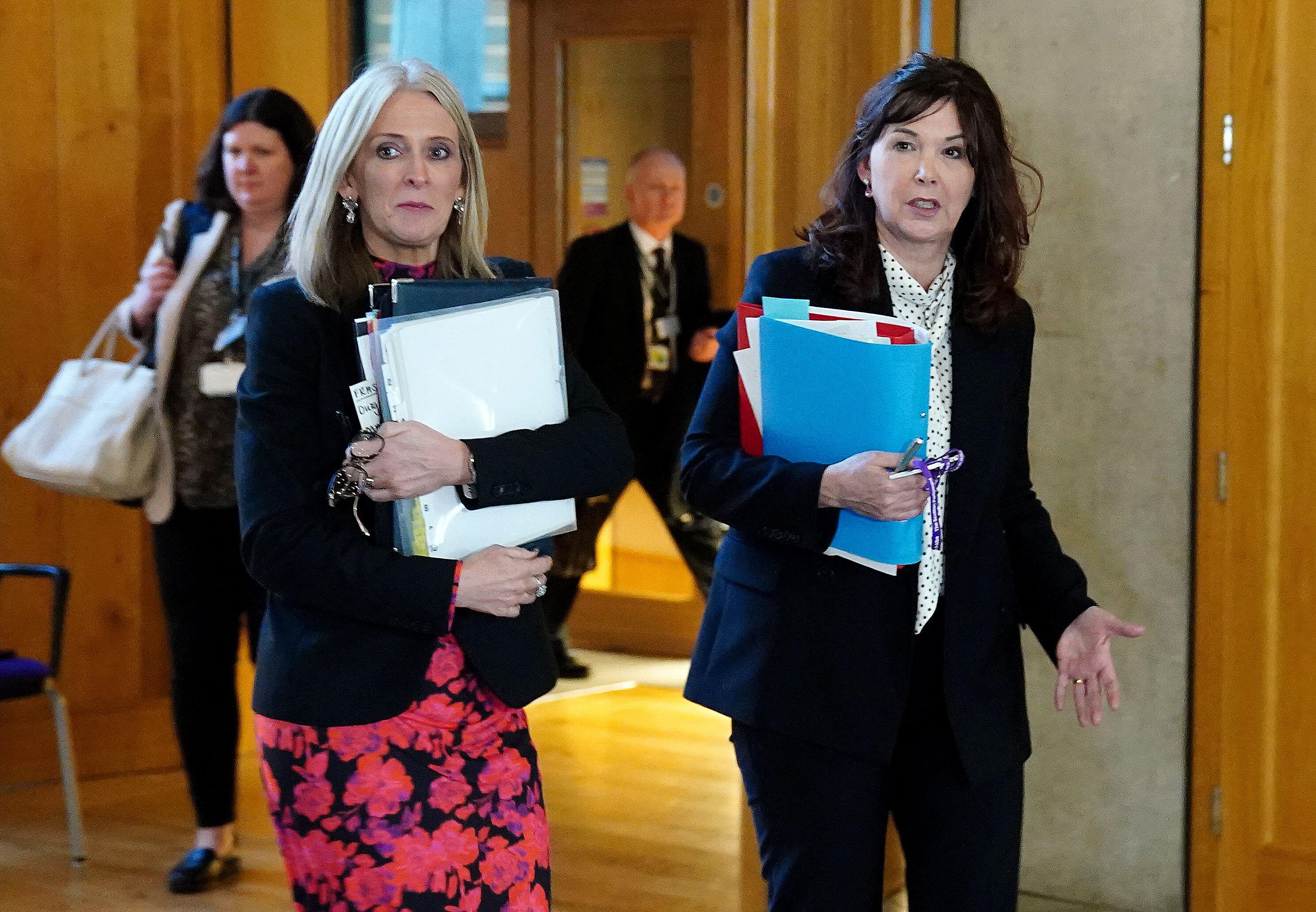

Ruth Charteris with Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain KC | Alamy

Charteris was speaking shortly after the Appeal Court agreed that corroboration rules should be updated to allow statements made by a victim during, or immediately after, an offence to be used as evidence in the resulting case. That decision came about as Constance announced that plans for a pilot for juryless trials in sexual violence cases would be dropped.

Conviction rates for sexual offending are “absolutely pitiful at times”, Charteris said, and while she understands why the pilot has been cancelled amidst opposition from the legal profession and across the benches in Holyrood, it would have been “a good thing”.

“The conviction rate for rape hovers at about 48 to 51 per cent, but that disguises the fact that in the case of single-complainer, single-accused rapes – often that’s acquaintance rapes – it’s down to as low as 24 per cent.

“That’s against a normal conviction rate of about 88 per cent. We are working hard to address it within the prosecution service.”

On what an all-woman top team means for the legal system, Charteris is thoughtful. “Most women are different from most men,” she said. “I think we do bring something different. It’s obviously right and good that we’re able to represent a cross-section of society. That makes sense. I’m not suggesting for one minute our predecessors who were male didn’t care.

I really stumbled into the law

“Maybe we are more attuned [to], and just a bit more conscious of things like sexual violence and offending rates and the absolutely pitiful, at times, rates of conviction and the difficulty of a few complainers’ journey through the justice system.”

After rising to such a senior position, it might be assumed that an ambitious young Charteris had always been aiming for the top of the legal world. In fact, she entered law school by chance, having gone to a University of Glasgow open day because she “got a day off school” to do so. “I don’t think I ever had any burning ambitions,” she said, though she toyed with the idea of journalism.

“I really stumbled into the law because my best friend at school was one of these really clever people who got five As, so the world was her oyster. We went to the Glasgow uni open day because we got the day off school, and she’d gone to the medicine faculty then she dragged me to the law faculty, and one of the very lovely lecturers, he was talking to her and then he turned to me and said, ‘what about you, do you not fancy doing law?’ He just took an interest in me, he kind of teased it all out of me, and I left thinking, ‘yeah, I really do want to do law, and actually I think I can do it’, so really it was a pretty lovely lecture who bothered to speak to me, and I thought, ‘yeah’.”

Charteris remembers being encouraged into education by her nurse mother and her social worker dad, who had qualified in his 40s. “Noone in my family had been to university, far less had any involvement whatsoever in the legal profession,” she said. “My dad went to Glasgow uni in his 40s to do social sciences. He always valued an education: he grew up in Paisley and basically had to leave school at 16 and went to work in the mills, but he was clever, and he was pretty sensitive. I think he always wanted to have education, so he always wanted it for myself and my sister and brother as well.

“We came from a very, very working-class background, lived in a council house in Cumbernauld. He became a social worker, which is a great job to do. Mum was an auxiliary nurse. We never had a car, I went to state school, but both of our parents very much encouraged us to just do our best.”

At the two-day International Law Enforcement in a Digital Age event | Andrew Perry

Does that sense of public service come from her parents? “Definitely,” said Charteris. “I don’t think money was ever a major deal for any of us, and I don’t say that to, you know, polish my halo and say, ‘look at me, I’m all about public service’, but genuinely, it was very much about making people’s lives better.”

As a student, she developed a passion for public law and the impact of human rights legislation – an interest which took her to the USA, where she worked with the Equal Justice Initiative non-profit in Alabama. The role involved working on death penalty cases at the appeal stage, something Charteris describes as “an eye-opener from every perspective”.

“I lived and worked in the community, Montgomery, Alabama, and it was just so fascinating to hear from a wide section of society about the civil rights movement and, of course, the Montgomery bus boycott and how it all burst onto the scene,” she said.

Most of the people she met, Charteris recalled, thought she was “off [her] head”: “At the church I attended they all thought, ‘oh she’s involved in this death penalty project’, and the people at the death penalty project thought, ‘what on earth is she going to church for?’ But I think I could be pretty objective and did try to see it from all different perspectives.

“The one case that really stuck in my mind was this appeal; this boy had been 15 when he was convicted of murdering one of his classmates. So, he’s a black boy convicted of murdering his white classmate. There was a newspaper clipping in the file and it was [a photo of] the mum of the victim hugging the mum of the convicted boy, really, essentially, both of them recognising that they each was going through a horrific experience, and essentially they had each lost a son.”

I do believe in justice

A member of the Free Church of Scotland, Charteris said it is her faith that gave her an early grasp of core legal concepts. “Growing up, I might not have heard much about law or lawyers, but I certainly heard a lot about justice and about accountability,” she said.

“Faith is really important to me. Lady Cosgrove, who was the first female judge, came from a Jewish background and she very much spoke about how she could relate to so much of what is pictured in the Bible about justice and ‘justice rolling down like water’. For my own part, the death penalty is a very nuanced and difficult subject. I don’t think there’s necessarily a Biblical warrant for it, but I do believe in justice and part of that has to be accountability.”

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe