Post Office Horizon: Should politicians play a role in exonerating Scottish victims?

It is a mark of just how scarring it was to be caught up in the Post Office Horizon scandal that so few of those impacted in Scotland have come forward to have their names cleared. Back in 2020 the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission (SCCRC) wrote to 73 former sub-postmasters convicted using Horizon evidence, telling them the case against them had likely been unsound and urging them to get in touch. Just 12 did.

Since then the road to exoneration has remained largely untravelled, with just six people having their cases overturned after the route to an appeal was cleared by the SCCRC. The commission has continued to ask those affected to make contact and the reaction to the ITV drama Mr Bates vs The Post Office, which captured the popular imagination when it aired just after Christmas, has shown that public opinion would be very much on their side if they did. Yet just two more cases have been referred to the appeal court and, while politicians at Holyrood and Westminster bicker over how best to acquit everybody involved, it seems clear that dozens of people impacted in Scotland just want to distance themselves from it all.

“It’s important that everyone realises that these folk went through life-changing experiences and some people react to that differently,” says solicitor Stuart Munro, who represented one of the six who has successfully appealed. “They have spent their lives being ashamed because of the tarring they have had, and they just don’t want to go back to that. That’s what’s been so difficult [recently] – the attention being put on this. The objective part of it is that this is great, but the subjective part is this is terrible.”

.jpg) Former sub-postmaster Alan Bates led the 2019 group litigation that resulted in the Horizon scandal finally being recognised | Alamy

Former sub-postmaster Alan Bates led the 2019 group litigation that resulted in the Horizon scandal finally being recognised | Alamy

By now most people are familiar with how the scandal unfolded. In 1999, following a three-year pilot, the Post Office started rolling out automated accounting system Horizon, a supposedly game-changing programme built by government contractor Fujitsu to centralise systems across the entire UK branch network. Almost immediately there was an increase in the number of sub-postmasters seeing unexplained accounting shortfalls and, rather than investigate whether there was an issue with the system itself, the Post Office accused the people forced to use it – people who were signed up to host Post Office branches within their own existing businesses – of theft. Hundreds were prosecuted for financial crimes, with the Post Office, which is wholly owned by the UK Government, leading those prosecutions itself in England. In Scotland – where the organisation is, like the police, one of many so-called specialist reporting agencies – it referred cases to the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS) to prosecute them on its behalf.

Though problems with the system had been highlighted over many years, the 2019 judgment in a group litigation led by Alan Bates – the Mr Bates of the TV series – confirmed it: Horizon was a flawed system and every conviction brought using its outputs as evidence was potentially unsound. The Post Office had, Mr Justice Fraser (now Lord Justice Fraser) ruled, “attacked and disparaged” sub-postmasters while engaging in the “21st century equivalent of maintaining that the earth is flat”.

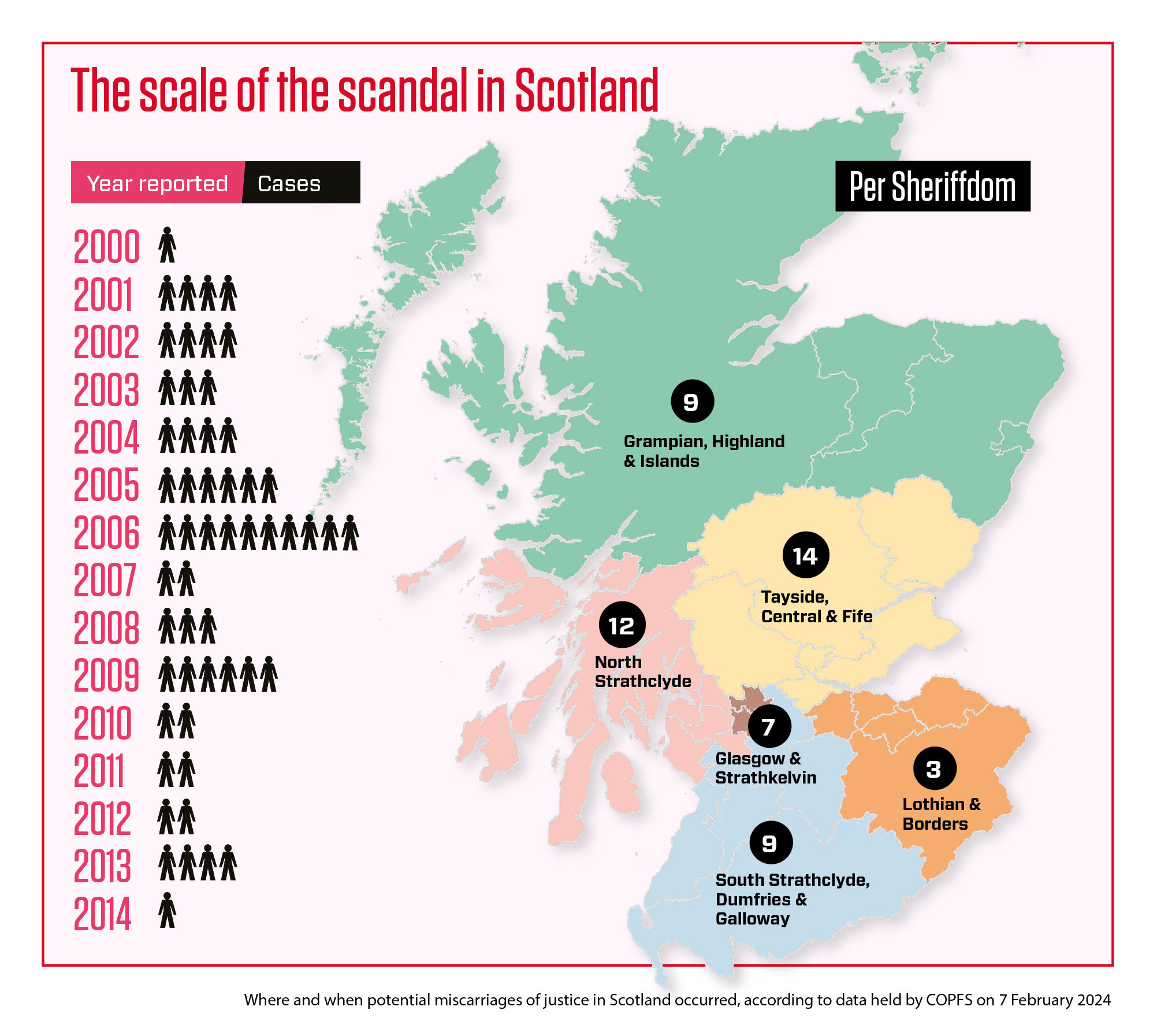

Nobody knows for sure how many people in Scotland were wrongly convicted due to Horizon evidence, but what is clear is that when their cases were originally heard the vast majority of affected sub-postmasters felt railroaded into conceding guilt. Figures provided by COPFS earlier this year show that of the 54 convictions that at that time were being defined as Horizon cases (that number has since reduced to 48) just one had gone to trial when it was originally brought – all the others had resulted in a conviction because the accused had pled. The reasons for that are almost impossible to unpick, with Munro stressing that it is “very difficult to reconstruct” what happened when looking back over 15 to 20 years. “People’s memories are not crystal clear,” he says.

What is certain, though, is that the Horizon cases started being prosecuted at a time when there was huge change afoot in the Scottish legal system. Court reforms that began in the mid-nineties and were consolidated by the Scottish Executive when parliament was reconvened in 1999 formalised the practice of sentence discounting, meaning there was a presumption towards giving lighter sentences to people who entered an early guilty plea. As the respected legal academic Fiona Leverick, who was then a lecturer at the University of Aberdeen but is now a professor at the University of Glasgow, wrote in the Edinburgh Law Review in 2004, one of the biggest problems with sentence discounting is that it can lead to innocent people pleading guilty. “It may be that an innocent accused person, faced with a choice between pleading guilty and contesting the prosecution case, will cut his or her losses, rather than risk receiving a sentence up to 50 per cent higher than otherwise would have been imposed,” she wrote.

At the same time, changes to the legal aid system introduced in 1999 brought in fixed fees for solicitors representing clients in criminal cases. The majority of the Horizon cases, which would not have been easy to group without hindsight given that they were dotted across sheriffdoms and heard at an average rate of four a year between 2000 and 2014, were prosecuted at the summary level. The rate paid for acting on such cases was set at £500 regardless of whether the accused went to trial or entered a plea. When faced with apparently incontrovertible evidence that their client had committed the offence they were accused of – and given the discount an early plea would bring – it would be unsurprising if solicitors had advised them to take the latter route. And the evidence was, apparently, incontrovertible.

“There’s a societal failure that we all fall into where if a computer says something we assume it must be right,” Munro says. “If you go to a lawyer and say you’re accused of something but you didn’t do it, they’ll say ‘okay, we’ll take it to trial’. But if the computer evidence said you should have X and you only had Y, the assumption was made that you had stolen it. Everyone proceeded on the basis that the computer system must be right.”

Now that everyone knows for sure the computer system was not right, politicians are clamouring to find a way to right the historic wrong. In England, where hundreds of sub-postmasters were prosecuted, such miscarriages are going to be overturned using legislation, with the UK Government publishing its Post Office (Horizon System) Offences Bill in March. The bill, which is expected to pass in the summer, will quash all Horizon convictions in England and Wales without the need for a court appeal, effectively overwriting the scandal in one fell swoop.

Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain KC updates parliament on the Scottish Horizon cases in January | Alamy

Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain KC updates parliament on the Scottish Horizon cases in January | Alamy

The Scottish Government, which is usually at pains to pass legislation independently of Westminster, was initially keen to see the UK bill copied into the Scottish statute book, with justice secretary Angela Constance writing a number of letters to Post Office minister Kevin Hollinrake to that effect. For SNP MP Marion Fellows, who chairs the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Post Offices and has repeatedly raised the plight of sub-postmasters in the Commons since the Bates judgment was handed down, it is the only way of ensuring fairness to all those affected. Drawing up separate legislation in Holyrood, which would have to be done after the UK bill has passed, would, she says, mean telling Scottish sub-postmasters “okay, you’ve waited, but you’ll have to wait longer”.

“Scottish victims should not have to wait any longer than victims across the rest of the United Kingdom,” she said during a Westminster debate last month. “If the Scottish Government were to expedite a bill in the Scottish Parliament without knowing exactly where this [UK] bill will end up […] then that would not be right either.”

First Minster Humza Yousaf appears to have conceded that separate Scottish legislation will be required, telling the Holyrood conveners’ group last month that, as the UK Government does not support extending its bill north, the Scottish Parliament may have to be recalled in the summer to come up with its own version. “The trouble with the timetabling of all of this is that the UK bill might well not conclude until the end of July,” he said. “Of course, this parliament would be in recess at that point, and therefore […] it would be up to the parliament to consider recall.”

Yet while Lord Advocate Dorothy Bain KC, who heads the Scottish prosecution service and is the government’s chief legal adviser, says that bringing forward legislation to quash wrongful convictions is “a matter for the Scottish Government”, it is clear that would not be her favoured choice. When she addressed parliament on the Horizon situation earlier this year, Bain noted that due process must be followed. In a statement provided to Holyrood she says that COPFS is “utilising the available and viable processes to achieve resolutions”.

Retired sheriff Douglas Cusine says it is right that the government should have no role to play in achieving those resolutions. “It is inappropriate for the Scottish Parliament or the UK Parliament to overturn convictions that were made in court,” he says. “It flies in the face of the separation of powers.” Kevin Drummond KC, who was also a sheriff before retiring from the bench in 2018, agrees. “Why have the politicians got themselves involved?” he asks. “This is a matter of pure law and the remedy lies in the hands of the lord advocate.”

Both, however, are critical of the way Bain has proceeded, saying that requiring every case to be reviewed by the SCCRC before being sent to the appeal court makes the process too long and unwieldy. The six successful appeals were all dealt with administratively, meaning they were not opposed by the Crown when they got to court and so were overturned without any evidence having to be led. Cusine and Drummond say that should pave the way for the remaining cases to be quashed in a similar way, suggesting that Bain could proactively ask the appeal court to overturn them rather than passively waiting to be asked for her department’s response.

Senior judge Lady Dorrian oversaw the six Scottish appeals that have already been succesful | Alamy

Senior judge Lady Dorrian oversaw the six Scottish appeals that have already been succesful | Alamy

As the number of Scottish cases is comparatively low, a legal solution would appear to the preferable choice, particularly when the problems with blanket legislation are factored in. Indeed, as Sir Jonathan Jones KC, the former head of the UK Government’s legal service, has pointed out, while the Westminster legislation “seeks to define with clarity the categories of conviction which are to be overturned, it does not name the individuals whose offences are overturned”. For legal commentator Joshua Rozenburg that is the “obvious and fundamental flaw” of the proposed solution as “although it will clear hundreds of people who were wrongly convicted, nobody will know who they are”. It is not enough for justice to be done, in other words, it must also be seen to be done. And, with both Hollinrake and Yousaf saying that legislation will necessarily sweep some guilty parties into acquittal along with the innocent, a court disposal is the only way of ensuring that that justice really is served.

COPFS insiders suggest an upcoming written opinion from senior judge Lady Dorrian, who oversaw the appeals that have already been successful, could turn the Scottish situation on its head, potentially clearing the way for Bain to take the kind of action Cusine and Drummond suggest. As things stand, though, the route to exoneration is not just painful, but painfully slow. It requires those who have been wronged to ask the SCCRC to review their situation before spending money on lawyers to fight what will inevitably become a very public case – all while the spectre of guilt hangs over them thanks to Hollinrake and Yousaf’s words. It is perhaps unsurprising that the number of applications the SCCRC has so far had to deal with is so low.

At the same time, a quashed conviction is hardly an end in itself. From the outside, the six Scottish sub-postmasters whose convictions have been overturned appear to be in a good place. Their names have been cleared, the public is on their side, and each is now entitled to claim £600,000 in amends-making money from the Post Office, which in addition to compensating those whose convictions are quashed is offering monetary redress to the many sub-postmasters who were affected by Horizon but were never actually prosecuted.

Scratch beneath the surface, though, and a far darker picture begins to emerge. Though they may have gained some kind of twisted – and unwanted – celebrity status due to being caught up in the scandal, when approached for this article two of those affected made it clear that discussing their situation was not something they were willing to contemplate, the passage of time and the ultimate acquittal doing little to ease the trauma of their experiences. Another, while initially minded to talk about the appeal process in order to help others navigate “the rocky road us victims need to ride to get justice”, later decided not to proceed.

“It means thinking about a subject that’s a big trigger for my PTSD,” they said. “Although I’m doing better, I’m far from recovering, if that will ever happen, [so] I need to decline as I need to prioritise my health.”

How exactly such a massive miscarriage of justice was able to unfold may never be fully understood. One thing is clear though: lawyers and politicians can argue the toss over who is best placed to right this incalculable wrong, but when it comes to rebuilding shattered lives no amount of pontificating – and no amount of money – can begin to make a difference.

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe