Dame Sue Black: I can’t wait for death

When Professor Sue Black was nine years old, she was raped by a man she vaguely knew. He left her alone and bleeding and with the threat ringing in her ears that she must never tell anyone. And she didn’t. Not for decades.

It was shocking and it was life-changing but was also something she adamantly refused, and refuses, to allow to define her. And while this extraordinary, award-winning forensic scientist, academic, author, peer, wife, mother, and now president of St John’s College, Oxford, who was awarded Scotland’s highest honour of being appointed the Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle in March, has undoubtedly succeeded in not being bound by that one act of brutality, there is no doubt that what happened that summer afternoon was a defining moment. A point at which she says her childhood ended and her adulthood began.

“It was absolutely hugely defining”, she tells me. “At the time of the incident, I was made to believe by the person that it was all my fault, it was all my responsibility, no one would believe me, and if I told people about it, they would call me a liar, and they’d think I was horrible and dirty. It was just classic control and at that age you don’t know that you’re being controlled. So, you just internalise it. And you live from that point forward, I’m afraid to say, as a victim and you’re always a victim, I don’t think it ever goes away. It’s the one thing people don’t understand because they’ll say, ‘oh, you’ll get over it’. But you never get over it, you suppress it. And every now and again, it will bubble to the surface.”

Black had largely successfully supressed what had happened to her that day, even keeping it from her mother for a decade, who didn’t believe her when she finally told her, until she surprised even herself by opening up publicly for the first time to former Scottish Conservative leader Ruth Davidson, who was interviewing Black for a book on powerful Scottish women in 2016. She then went onto write about it herself in one of her many books, an autobiography, Written in Bone. In it, Black described how she chose to “own both the physical and mental pain” rather than reveal what a delivery driver, a regular visitor to her parent’s hotel, had done to her, leaving “warm blood trickling down my legs and a crushing sense of shame mixed with fear”.

“I had no intention of writing that in the book,” she says. “Often writers say when you are into a book, it starts to write itself. So, when I was writing a section on the long bones and was talking about being in the mortuary looking at the X-ray of a child who had committed suicide, it seemed natural to talk about it.”

The link was that Black had spotted Harris lines, markers of trauma, on the child’s bones, the regularity of which indicated an annual event, ultimately leading to the imprisonment of a relative who had looked after and abused the child when the parents were on holiday. Over time the lines disappear, but as the child had died close to the time of the abuse, they were still present.

Black naturally questioned whether her own bones would reveal her secret. “Did I have Harris lines? Yeah, I probably did, and they are no longer there because the bones will have remodelled themselves long ago. It wasn’t that I was trying to shock or finally reveal. It was that at the age 59, as I was then, it was in the past.”

Her bones may no longer show the marks of that trauma, but how did it change her, as a person?

“That’s a really interesting question. You know, with a huge amount of hindsight, of course, it did make me more independent. I think it probably made me less trusting. I think it’s had a significant impact on my life in lots of different ways. And I do look through a lens now and see behaviours, both from men and women and others that I think, please don’t do that, you’re putting yourself in a situation that’s difficult, or please don’t objectify that woman that way, she’s more than an object. I see behaviors now as a mature adult that I didn’t see back then but I guess it made me look at the world through a different lens.”

It would be easy to apply some pop psychology to all of the above and draw a straight line from that early assault to Black’s eventual career in forensics and her role in understanding the consequences of trauma on the body, and in doing so helping solve some of the grisliest of crimes including child abuse, but it would be an incorrect assumption.

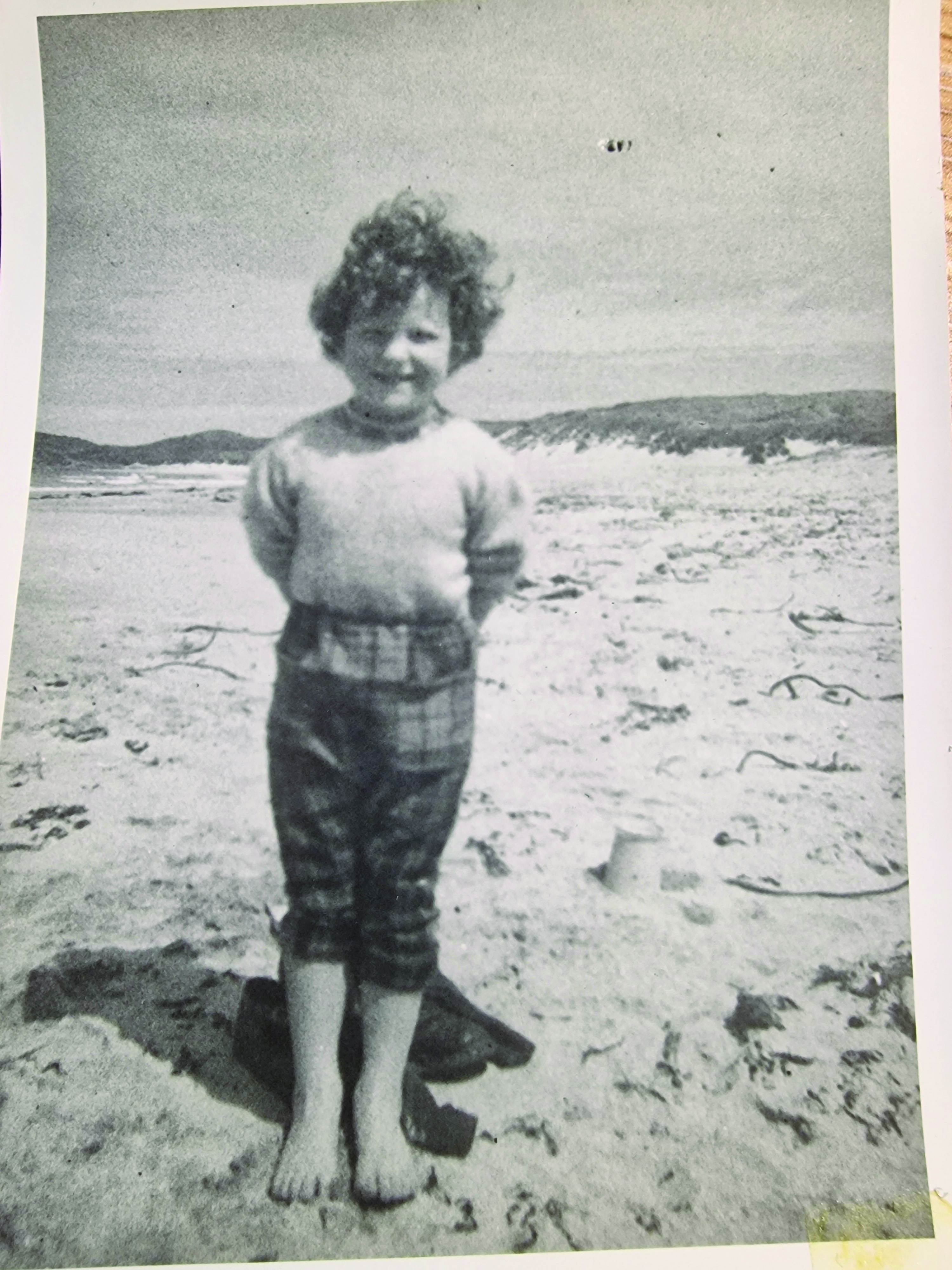

Indeed, Black describes her childhood to me as “the most marvellous time”. As a child, she loved nothing more than sitting with her father at the back door of their west coast home skinning a rabbit or plucking a pheasant and getting blood on her hands. The gutting process that might have turned the stomach of most of her childhood peers was wrapped up in her adoration of her father and an insatiable appetite to be around him.

She was, she says, her father’s “little shadow”. He was, appropriately enough given their surname of Gunn, a keen shot and his young daughter would accompany him on the shoot.

“I loved my mother, but I adored my father, and wherever he went, I would follow. I would go out with my dad if he went shooting, and it would be for things like rabbits or pigeons or whatever, and always for the pot. He would teach me sitting at the back door how to skin a rabbit, pluck a pigeon or whatever, and from a very young age I was always around dead things. I had blood on my hands from a very early age and it never bothered me. I loved it. Skinning dead things was just a natural part of the extension of my time with him.

I spent the entirety of my teenage years in the butcher’s shop, so I have always been around dead things

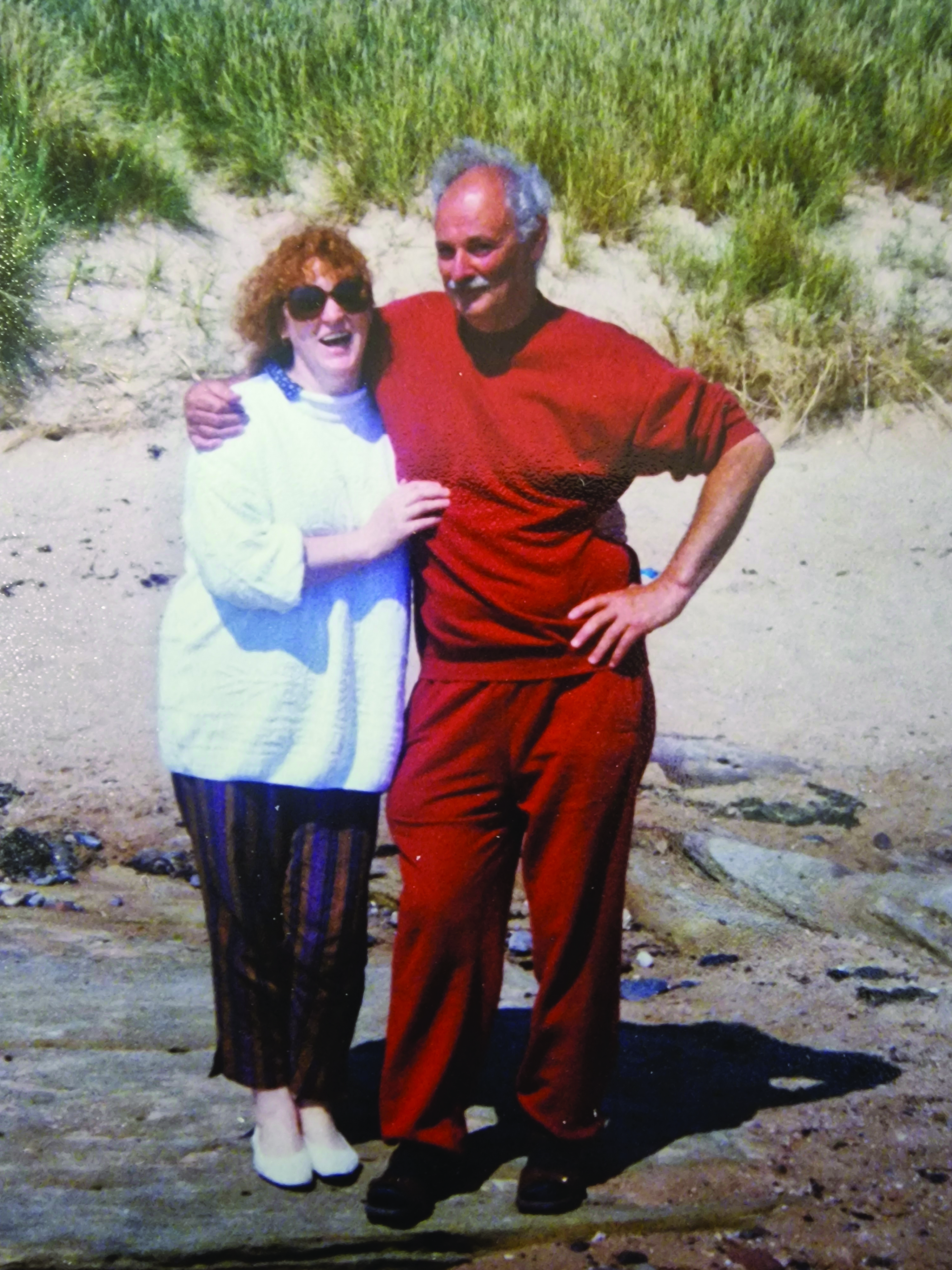

“My father was a very practical man – ex military service, 6’2”, barrel-chested, moustache – a practical man who liked doing things. I can’t remember my father ever holding my hand or hugging me. Men of that generation didn’t do that. He showed he cared for me by doing things with me, spending time with me. That was his gift.

“I naturally loved my mother, but it was a different relationship than with my dad. She was quite a needy character in her own way. Her mother died of sepsis during childbirth, and I think she always carried the responsibility for that. And so my mother was brought up by her father who died when she was two of scarlet fever and she was then brought up by her grandmother, and then her grandmother died of old age so basically she had lost the three people who cared for her when she was very young and she then lived with her aunt and uncle who had no children and just worshipped her and she had a lovely childhood, very caring, but I think having lost a mother, a father, and a grandparent, there was a part of her that never felt complete, so she was quite needy in her own way. She wasn’t overly independent, she needed to have people around her. She was a very caring woman and would have given you the shirt off her back if she could and she showed she loved you by cooking for you. She was a great cook.

“When I was 12 my father said to me, ‘what job are you going to get?’ And he meant there and then, whereas I thought he meant when I left school, and his approach was basically that you are of an age to work, and I expect you to give your mother half your money for board and lodgings and so that’s what I did, and my first job was in a butcher’s shop. It just fitted perfectly for me. I spent the entirety of my teenage years in the butcher’s shop, so I have always been around dead things, and I love the smell of a butcher’s shop to this day.

“So, in answer to your earlier question, my career path didn’t come from a place of trauma, it came entirely from sitting at the back door with my father skinning rabbits and then working in a butcher shop. For me, my career stemmed from areas of fun and pleasure and family and community and doing things that I was really comfortable doing.

“I went to Inverness Royal Academy and my biology teacher, Dr Fraser – I just adored him, and I still speak with Dr Fraser, he’s a dear friend now, which is lovely – he said to me, ‘you need to go to university’. I didn’t even know what university was. So, why the heck would I go there? My mother expected me to leave school, get a job, marry somebody, have children and live five minutes away from her. That’s what she wanted. But Dr Fraser said, go to university. And because I so admired him as a teacher, he was a brilliant teacher, I knew it would be something biology based.

“Anyway, I got to the end of my second year, and I had subjects that just didn’t float my boat. I was doing zoology and genetics and chemistry, and soil science, and it was just so utterly not me. At the end of it, going into third year and had to choose a subject to major in and the only two things that I felt I was any good at was botany, which could never have been my future, and I’d done a course in histology, in anatomy, and so I went to see both sets of tutors, and the botanist convinced me that was never going to be my future, because I was not going to be interested in plants.

“And when the anatomist said to me, ‘in your third year, you go into the dissecting room and you dissect a human body, top of the head to the bottom of the toe’, I thought, I can do that. I know I can do that, because it’s the butcher shop. It’s a different animal, but it’s the butcher shop. It’s knives, it’s saws, it’s muscle, it’s bone, it’s skin, it’s fat, all the things that I felt really comfortable with thanks to my father and the butcher’s shop.

You need to find the evidence, recover the evidence, analyse it, present it, and go home. I thought that was the best advice I was ever given

“It’s not about delighting in the grimness of death for me, there’s no goth in me. It’s not that sort of thing at all. For me, I love the precision of the butcher shop. So, if you watch the butchers, they knew exactly where to place the knife to remove the bit of meat that would become brisket. There was a real precision.

“When I went into the dissecting room for the first time, it was like crossing the Rubicon. I walked into that room and there were 50 tables, and they all had a white sheet with a mound underneath them. I knew they were dead bodies. I’d never seen a dead body before other than rabbits and pheasants and things like that, and I remember thinking, I don’t know how I’m going to react to this. I don’t know how I’ll cope. So, you pop the blade onto the scalpel, and you pull the cover back, and you’re faced with a human and that first time that you cut through the skin, there’s a moment where you think, actually, I’m okay. In fact, you know, this is fascinating. Oh, I wonder what that is, where does that connect to? And before you know it, you’ve forgotten to be afraid because the world and society says, ‘oh, it’s anatomy, it’s bodies, it’s going to be really creepy and spooky’. It’s not, it’s fascinating. And the world just opened for me, and I knew I was in the right place.”

I mention that it’s interesting that for someone who has spent much of their professional life rummaging around in the inside of dead bodies, Black is clearly as interested in a person’s emotional make-up as their physical body parts.

“I’m interested in it all really. It’s a bit of both, isn’t it? Because the job that I did, because it’s slightly different from the job that I do now, but the job that I did, there is a hugely emotional side to it and whenever it involves people there’s always to be an understanding of the holistic person. So, whilst we’re doing a physical job, we’re also trying to understand rationale, actions, emotions, interaction between people. So, it’s kind of all in there, piecing together who this was and what happened to them and why.”

I ask her if it is necessary to compartmentalise the emotional from the physical when often in some of the cases she has been involved in there will be grieving relatives looking for answers.

“I think, as much as you can. I was very lucky early on in my career, a chap called Charlie Hepburn, who was head of CID in Northern, when we had a northern police force, I’d said to Charlie that I was going to do these cases. And I can remember him looking at me and sort of shaking his head and going, ‘Oh, Susie’. Nobody called me Susie, but he said, ‘Susie, don’t do it’. He said that once all of these things get inside your head, you’ll never get rid of them. But he also said that I wasn’t going to listen to him because ‘you’re a redheaded, irascible Celtic woman’. He then gave me a really good bit of advice which was don’t own the guilt. It’s not your fault. You didn’t cause it. You couldn’t stop it. No one’s asking you to become personally involved in this. You’re here because of who you are. You need to find the evidence, recover the evidence, analyse it, present it, and go home. I thought that was the best advice I was ever given. Don’t become personally involved, if you can help it at all. But I also like to think that what I have inside my head is a clinical box, and I leave my world outside when I go into it and I close the door, do what I have to do, and then come out and close the door behind me. But I’m also not so arrogant or naive to not think that somewhere along the line I might not close the door properly, and either my personal life comes in or my professional life comes out.”

In 1999 Black was the lead forensic anthropologist during the international war crimes investigations in Kosovo, which was particularly gruelling when bodies were being exhumed from mass graves. She describes that time as a pivotal point emotionally when she relied on her husband and children at home to keep her grounded.

“It was particularly hard not to be impacted by the emotion in Kosovo, because normally, in a forensic scenario, we’re in the mortuary and we’re removed from family, we’re removed from the outside world. You can afford to just be clinical, but when you’re actually at the crime scene where you’ve got families at the graveside, you’ve got military protecting you, you’ve got militia wanting to sniper you, and they’ve left you grenades, left you razor blades, explosive devices, those sorts of things, and you know you’re in the middle of a post-war scenario and that there’s still the risk associated with it, so you have to have an awareness of all those thing, but you do try to do your job independent of what’s going on.

“There’s no doubt those families would have wanted us to do things differently, but we were there under the auspices of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, and they were who we were there to serve through the auspices of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. I’m always very aware of who is my master, who is my boss, and what I am there to do. But at the same time, there is this innate sense of humanity, of doing the best you can for everybody and serving justice, because that’s what you’re there for, but also making sure that you don’t say or do anything that will cause additional grief.

On death itself? Gosh, I can’t wait. I really can’t. It’s going to be fantastic

“I can remember, and it’s actually quite a poignant moment in some ways, we were lifting a body out of the ground, and the family were around and because of the state of decomposition, I realised that the head was about to fall off. I literally ran in and, as they were lifting the body out, I held the head. It’s that realisation there are people watching, and if that head was to detach, which was nobody’s fault, there is going to be an extra sense of horror and grief to families. So, if I can prevent it, I’ve not got in the way of justice but I have managed to deflect that situation from that family. It was awful for everybody, and that particular moment was hard.

“I vowed at that point in Kosovo that my daughters would never go to sleep without a cuddle and a hug from somebody who would tell them that they were loved, because there were so many families that just didn’t have that any more. They were my grounding. That was me saying, learn from the horrendous scenarios of what’s going around you and think yourself fortunate, because I was. I stopped caring whether the hoovering got done or the dusting got done, or if there was a scratch on the car. I really didn’t care. But I cared if my children didn’t get a story before they went to bed or were told they were loved. It really changed my perspective on what was my role and my responsibility at home, as opposed to my role and responsibility in work.”

I ask Black if there are dead people who continue to live on in her head.

“There are many of them, that is the trouble. And they tend to be the ones where we’ve had a body, and we can’t identify who they were, and they remain unnamed. We found a young man from Balmore, and he had a noose around his neck. We suspect he committed suicide. And you think, this is a young man, there has to be somebody, somewhere, who cared about him, and yet we’ve never been able to get his name. People like that sit like a burr underneath my saddle. But also, it’s the cases where you know somebody’s missing, like little Moira Anderson, who went missing in the area around Coatbridge, that you know there’s a body, and no matter how many times you search, you can’t find it. Those are the ones that stick with you because you’ve not got closure.”

Being so all-consumed by death, I wonder what it has taught Black about life.

“Oh, I have learnt that life is wonderful! You only get one chance at it and if we spend our life miserable, then what a waste. Living is for now. And I’ve learned with age that you shouldn’t wait for five years or 10 years or whatever to do things you want to do, because you might not have it. That’s the one thing you learn in our job, that life can go in a second.

“I have also learnt that I love people. People are fascinating things, alive or dead. The one difference is that I never worry about the dead, because the dead are incredibly well-behaved. Whilst novels and movies make the dead scary, actually they’re not at all scary. They really aren’t. The things that scare me are what the living are capable of doing. So, the living scare me. The dead don’t.

“On death itself? Gosh, I can’t wait. I really can’t. It’s going to be fantastic. I want to know, what does it feel like; what does it smell like; what does it taste like; what does it look like? I spent my life on the other side of it, when people have made that passage themselves and nobody’s going to do it for me, I have to do it myself and therefore I’m not in any hurry to encourage it, but I’m really looking forward to the day that I can think, ‘so, this is what it is’.”

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe