'A plague on all your houses is the feeling we’ve got from quite a number of voters'

The dearth of enthusiasm has been the defining feature of this general election. In part that’s because for a long time it has felt like the outcome is already decided. Indeed, the idea that Keir Starmer won’t be entering 10 Downing Street on Friday morning seems nigh on impossible – a fact that even senior Conservatives have accepted as they seek to mitigate the damage to their own party by warning of some sort of Labour “supermajority”.

While the major question UK-wide seems to be how big a majority Starmer’s party will win, in Scotland the race is very different indeed. The only certainty here is that, in almost all of the 57 Scottish seats, those contests are going to be close. Very close.

Scotland-specific polling has repeatedly put the SNP and Labour neck and neck for much of the last year, according to polling aggregator Ballot Box Scotland. Even before this shift, many of Scotland’s Westminster seats were considered marginal – over a third of Scottish MPs from the 2019 cohort had a majority of fewer than 10 points.

The difference between the SNP winning 20 seats and SNP winning 30 seats isn’t as big as that might feel

With Labour recovering in the polls since then, combined with SNP decline, many more seats feel up for grabs. Nowhere is this more perfectly illustrated than the series of MRP polls that have shown huge variation in results.

At the disaster end for the SNP was Savanta, which put the party on just eight seats – only two more than it had pre-2015 – while Labour would rocket to 41. Yet an MRP from

WeThink had the SNP just scraping a majority of seats, 29, with Labour on 23.

Others, including YouGov, Ipsos and More in Common, all gave Labour the edge over the SNP though the number of seats was closer than Savanta. The results for the Conservatives and Lib Dems vary too – either party could get anywhere between one and five seats, pollsters believe.

This election is the first time MRP polls – short for multi-level regression and post-stratification – have been widespread, and it’s also a relatively new type of modelling, which goes some way to explaining the variation in results. But it’s also a sign of how many seats are on a knife-edge.

What those headline figures hide is how many seats are too close to call. Depending on the pollster, that number ranges between 12 and 27 – introducing a not insignificant degree of uncertainty into their projections.

Mark McGeoghegan, a polling expert from the University of Glasgow, explains: “What we can take away from the polls as a whole, particularly looking at the Scotland-only polling over the course of the campaign, is it’s going to be quite close in terms of seats between the SNP and Labour. Lots of these seats are very marginal, they’re going to be very closely fought contests, and we expect these contests to correlate with each other – say one seat happens to go to the SNP, we’d expect that to happen to other contests that are similar. Therefore, the difference between the SNP winning 20 seats and SNP winning 30 seats isn’t as big as that might feel.”

McGeoghegan explains there is a “tipping point” effect at play. In other words, if one urban central belt seat goes one way, other urban central belt seats are likely to have voted the same way. This means a percentage point either way for Labour or the SNP nationally will make a big difference in seat numbers despite the difference in raw votes being relatively small.

On the campaign trail

Despite the evidence that Scottish Labour had been closing in on the SNP for the last year, the necessary change in message for the election appears to have taken some of the nationalists by surprise. As recently as March, former SNP leader Humza Yousaf was urging members to go out campaigning with the message of making Scotland “Tory-free”. Labour was barely mentioned.

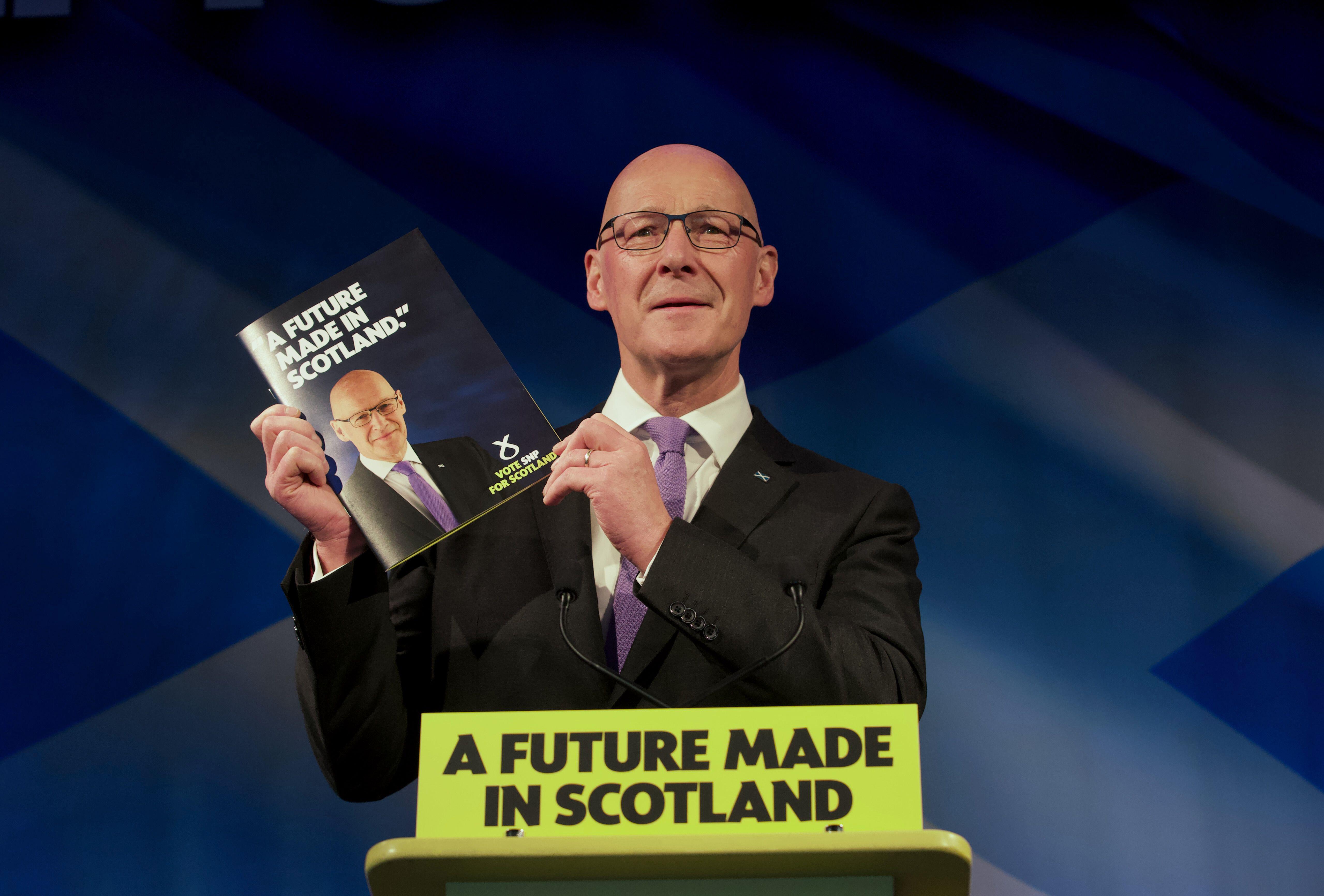

Fast-forward a few months to the SNP’s manifesto launch in Edinburgh, and the penny has finally dropped. John Swinney, facing a major electoral test in what are still the early days of his (albeit second turn at) leadership, focused his comments on ending the two-child benefit cap and funding for the NHS – both, the SNP believes, weak points for Labour that can be exploited.

The problem for the SNP at any Westminster election is that the party won’t be in power come Friday. While this point has been sidelined for almost a decade while independence was a salient issue, current polling suggests that many Scots may be starting to return to pre-referendum voting patterns. McGeoghegan says there is evidence that the electorate consider which level of government they are voting for: “There will be a chunk of voters who will vote in quite a sophisticated manner, and both vote for Labour at Westminster and for the SNP at Holyrood.”

This is positive news for Labour, for now at least, as the party has struggled to find its place in Scottish politics post-referendum. With the mood across the UK being very much anti-Conservative above all else, Scottish Labour leader Anas Sarwar has been able to set out a sincere pitch to pro-independence folk that this is an opportunity to remove the Tories without needing to agree with his party on the constitution.

Yet while Scottish Labour is feeling buoyed by the polls, this could be a double-edged sword. Polls can over-inflate expectations, and if Labour doesn’t come ahead of the SNP it will broadly be seen as a defeat even if it makes significant gains. And all the signs – high voter apathy, a lack of enthusiasm for leaders, and an assumed foregone conclusion – are that voter turnout will be lower than in recent years. While this problem is unlikely to matter for the overall UK result (Tony Blair swept to victory in 1997 despite lower turnout than 1992), it could have significant consequences in Scotland given how close most seats will be.

The Scottish Conservatives, in contrast, may benefit from low expectations. It’s difficult to imagine a worse campaign for the Tories, including the party’s Scottish leader Douglas Ross fumbling his own candidate announcement due to the optics of replacing a hospitalised incumbent. Despite this, the party may not be on track for total wipeout (and retaining at least some of its seats would be a victory) because as much as its vote is down, so is the SNP’s.

And that is precisely why the Scottish Conservatives’ manifesto launch last week largely focused on the Scottish Government’s record. Indeed, of the five priorities listed on page two, four and a half of them relate to devolved issues. Only the last, on tax, mentions a reserved matter (National Insurance).

The problem is that whatever Ross says of the SNP, almost the exact same could be said of his party in UK Government. “This is your chance to make the SNP pay the price for 17 years of failure,” his manifesto foreword states. Not to mention that he is content for the SNP “obsession” about independence to continue because that bolsters his own vote; the higher up the constitution is on the agenda, the better the Scottish Conservatives do.

Despite the efforts to focus on policy, however, this election has been surprisingly policy-light. Instead of wall-to-wall pledges and offerings, the electorate has been treated to almost daily gaffes and blunders. And perhaps that’s connected to the other main story of the election being more about the size of the Labour landslide.

With Labour so far ahead, it has almost become irrelevant what Starmer would actually do with the power he’s about to be handed. The “change” slogan has worked – the country looks set to vote for a change in government, even if unclear on what that means. And with Labour pursuing a largely safety-first campaign – no rabbits out of the hat – and attempting to head off any Tory attack line before they happen, that has created a landscape in which other events have come to the fore.

The Tories have undoubtedly suffered most from this, from the way a drenched Sunak announced the election, to him leaving D-Day commemorations early, to the continuing row over election betting.

While these have had the biggest cut-through with voters, Labour hasn’t got out unscathed either. It has had to drop one of its candidates for betting against his own victory in the light of gamble-gate. There was also the will they/won’t they over Diane Abbott’s candidacy at the start of the campaign, and more recently as the question of gender reform once again raised its head, the party found itself in a muddle, leading to JK Rowling admitting she would struggle to vote for it.

But even these asides have done little to alter the landscape. Labour is still riding high in the polls and the Tories have not dropped any lower.

Ones to watch

Back in Scotland, there are three seats worth watching that should tell us a lot about the story of the election, according to McGeoghegan. “Broadly you can look at the election in Scotland right now as being essentially three separate contests between the SNP and each of the major unionist parties which are strong in different parts of the country,” he explains. “I picked three seats drawn from these battlegrounds.”

These are Paisley and Renfrewshire South, Aberdeenshire North and Moray East, and Mid Dunbartonshire.

The first is a Labour-SNP battleground. Paisley and Renfrewshire South is the location of one of Labour’s greatest losses in the 2015 election, when then 20-year-old student Mhairi Black toppled heavyweight Douglas Alexander. Black, having held the seat for almost a decade, is stepping back from politics and Alexander is standing in a seat elsewhere – so this race is between SNP councillor Jacqueline Cameron and Labour NEC member Johanna Baxter.

McGeoghegan says: “It’s a seat that for a long time was very strongly Labour and has more recently been very strongly SNP, and there’s a very large number of those SNP-Labour swing voters that we’re really interested in, not just in this constituency but across the rest of the central belt.

“Because of its closeness, you can use it as a tipping point. If we see Labour win Paisley and Renfrewshire South, that would give us a much greater confidence that they’re going to win lots of seats across the central belt – and if they don’t win it, that would give us some confidence that actually the SNP vote is holding up better than we expected in these more urban parts of the country.”

If even a handful of local voters vote for Reform, then they will increase the chances of the SNP winning

Aberdeenshire North and Moray East is the seat Ross is standing in, facing a challenge from the SNP’s Seamus Logan. If Ross retains the seat, McGeoghegan expects the Scottish Tories to hold on to most (if not all) its other seats.

Speaking to Holyrood, Logan says while he is not “confident” in winning, he is “certainly optimistic”. Toppling Ross would be a substantial scalp on election night and local factors play into Logan’s hands – not just how Ross became the candidate, but that Labour has withdrawn support for its candidate, Andy Brown, due to controversial posts on social media. Logan adds: “There are things going on but they’re not going to distract us… However, I wouldn’t deny that either of those things might in the long run actually help us.”

There’s also the prospect of a strong Reform vote in the area taking votes away from the Conservatives. That’s why Ross has spent a fair chunk of time warning voters off backing the right-wing outfit. He told Holyrood: “A vote for Reform in this constituency – or anywhere in Scotland – is a vote for the SNP. If even a handful of local voters vote for Reform, then they will increase the chances of the SNP winning.”

A well-placed insider in the Conservatives’ campaign admitted the party isn’t at all confident about retaining the seat because of Reform, as well as the fact that many voters won’t turn up because they are fed up with politicians. This view was echoed by Logan, who said: “Quite a lot of people are very disillusioned with politics generally, with all parties, sort of a plague on all your houses is the feeling we’ve got from quite a number of voters.”

And finally, the Mid Dunbartonshire seat is a fight between the SNP and Lib Dems. It is largely (bar slight boundary changes) the seat infamously lost by Lib Dem leader Jo Swinson to the SNP’s Amy Callaghan in 2019.

The different battle Callaghan faces to the rest of her colleagues is one she’s particularly aware of. Asked how her campaign is going, she told Holyrood: “People want rid of the Tories, don’t they? Sometimes that makes them decide to vote for Labour – that doesn’t work in Mid Dunbartonshire and people are realistic about that. They know that they either vote SNP or Liberal Democrat in Mid Dunbartonshire. But we know that they do that to get rid of the Tory government. It’s just how they get rid of the Tory government.”

The SNP don’t seem to have an awful lot to say in this election, but they’ll have an awful lot to say between now and 2026

The Lib Dems winning here won’t necessarily mean the party is on track to do well everywhere – the way it wins seats is via a highly concentrated vote in a few small pockets. But the party is hard at work, with candidate Susan Murray unavailable for interview as she is “concentrating on speaking to voters”.

But if the SNP wins here, like with Paisley and Renfrewshire South, it would signal the party is doing better than the polls currently project.

What next?

Whether or not Labour makes a breakthrough in terms of Scottish seats at this election, it is clear the party has enjoyed something of a revival. That much is evident from the demeanor of its politicians to the way businesses are buying into the party again.

But the next big question for Labour is how it will carry that momentum through to 2026. On the whole, voters aren’t backing the party at this election due to any great love for it or its leadership, but rather as a protest vote. McGeoghegan believes the Labour vote is currently “pretty unstable… without much glue holding it together apart from being an anti-Conservative vote”.

“The composition of the Labour voter coalition, the fact that it straddles quite strongly unionist voters and quite strongly pro-independence voters, that’s not a problem in an election where the aim of voters is to get rid of the Conservative government at Westminster,” he says. “But that may be a problem in the future for Labour if independence becomes a more prominent issue again or in a Holyrood election where voters are going to be asked to kick out a pro-independence government, not a Conservative government.”

He continues: “It’s not necessarily going to be the case that we can look at the result of this election and think, well, Labour have won back the central belt and because they won back the central belt, they’re going to be the biggest party in 2026. If there was a Scottish Parliament election tomorrow, they wouldn’t vote for them.

“And likewise, there’s a lot of water to flow under the bridge between now and 2026. The SNP don’t seem to have an awful lot to say in this election, but they’ll have an awful lot to say between now and 2026 to seem a bit more focused on the economy, a bit more focused on bread-and-butter issues, and trying to win voters back.”

In most Scottish Parliament polling at the moment, the SNP enjoys a narrow lead or is neck and neck with Labour. That could mean that, after nearly a decade of foregone conclusions at Scottish elections, in 2026 there will be all to play for. Both parties may want to find some enthusiasm before then.

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe