Ten years on from indyref, neither side has articulated a positive vision of Scotland's future

The day after the referendum in 2014 I asked this question of colleagues from Downing Street and the rest of the Better Together campaign: how do we keep this going?

I was met with quizzical looks. Eyebrows raised above smiling eyes and facetious grins. “But we’ve won,” they said.

“But the other side aren’t going to stop,” I said.

For many of my colleagues, the idea of continuing to campaign was a sick joke. They hadn’t enjoyed their time in what was seen as an unpleasant and unnecessary task. The job was done, time to pack up the tents and hand out the medals.

A decade on and I have no smugness in saying that my blindingly obvious assertion has proved right. The referendum was seismic but not final.

I feared two other things back then, only one of which has come true.

Firstly, that as a result of the referendum the SNP would win elections almost in perpetuity. Only now does it look like there is a chance – a chance – it won’t be the biggest party after the UK general election.

The second was that the SNP Scottish Government would go on a programme of subtle but profound reform to make Scotland so different from the rest of the UK, the step to independence could appear small.

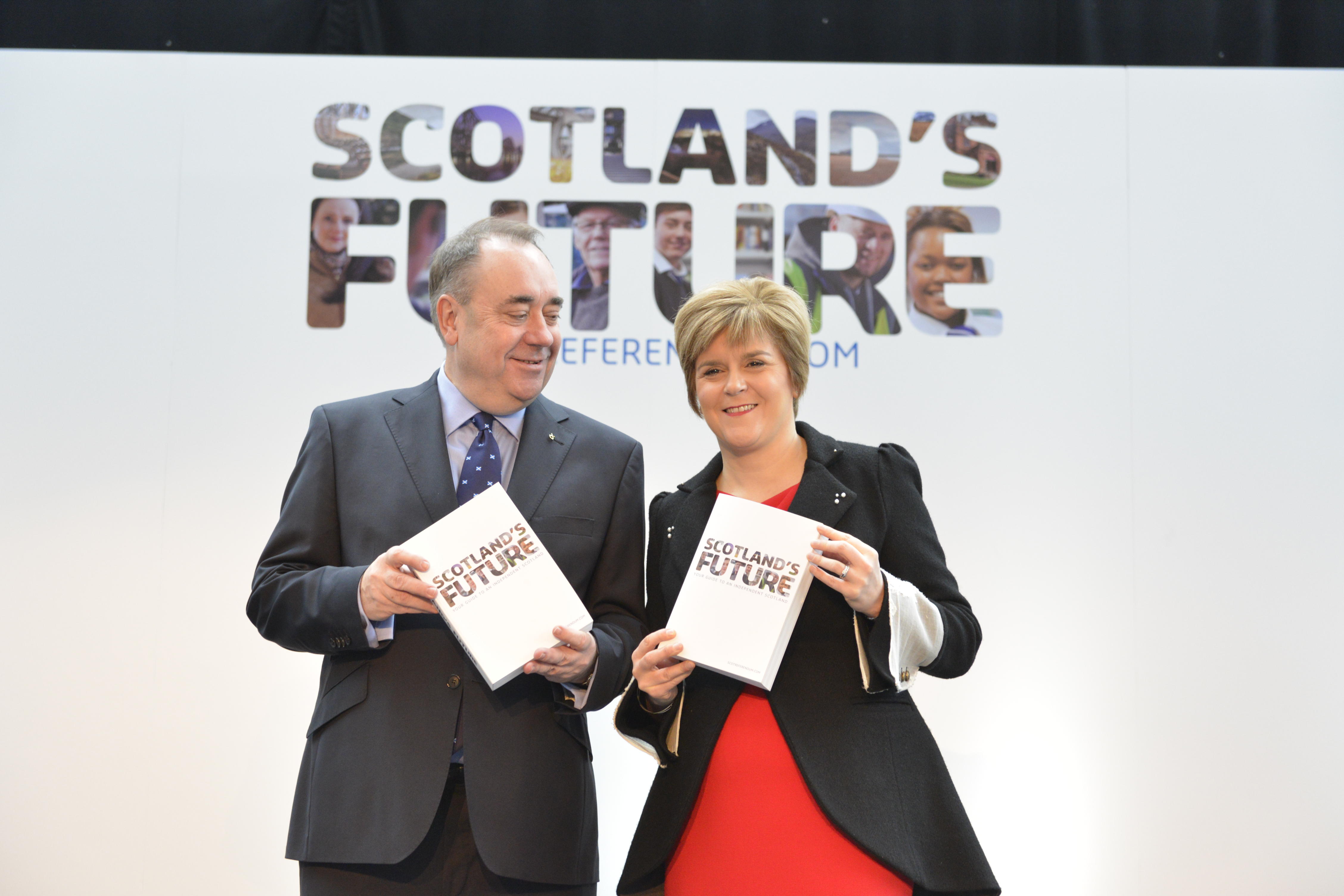

That hasn’t happened. I hadn’t factored in Nicola Sturgeon’s complete indifference to the business of government and that she would use her selfie stick as her pre-eminent lever of power. Arguably she has been the best passive safeguard for the union.

Despite that, if anything, support for independence has gone up slightly although the urgency behind it has slackened as it slips back in people’s priorities. Nonetheless, around half of Scots believe in leaving the UK.

But there is something else interesting to note which frustrates politicians on both sides. SNP strategists can’t find a way of getting yes supporters to back their party any more.

And for Labour, despite the SNP’s failures in office, former supporters who crossed the rubicon when they voted ‘yes’ don’t seem keen on returning to their old party even for a day trip, let alone to stay, in significant enough numbers.

We are in stasis.

It appears to be enough for the Scottish Government to blame Covid, or the Tories, and say things are better here than in Labour-run Wales.

Scottish Labour hopes that if it says change is coming enough times, people will believe it without it needing to describe what that change is. It says Scotland is “caught between two failing governments” – a line first used in 2015 when Scottish Labour lost 40 of its 41 seats.

I would suggest Scotland is instead caught between two inchoate ideas. Neither side’s vision is complete.

The nationalists still rely on the Tory bogeyman to garner support for secession, suggesting that things couldn’t get worse after separation rather than how they might get better.

They’ve never come up with a compelling argument on how they would address the deficit and what currency we would use, and Sturgeon’s idea of giving the problem to a PR man to solve while calling him an ‘economist’ was not the answer.

But nothing has developed on the pro-union side either. What is the positive case for Scotland staying in the union as the post-Brexit UK’s global status seems to wane?

The deficit and the currency are strong negative arguments but there needs to be more. Those are arguments about what Scotland can’t do, a brick wall rather than a gateway to better things.

There needs to be the air of Scottish possibility which the golden generation of John Smith, Donald Dewar and Robin Cook so embodied. A positive future in the UK.

And if anybody on the pro-union side thinks currency is the killer argument, that no one can win a referendum without a credible economic plan, I offer you the Brexit referendum of 2016.

Yes, they can.

Labour looks a certainty to win the UK general election, but if Scottish Labour does not become the biggest party in Scotland, for the first time the SNP will be able to coin the phrase: “A Labour government Scotland didn’t vote for.”

Given the state of the public finances, the first two years of a Keir Starmer premiership are likely to be tough, with a focus on England if he goes ahead with his plans for planning reform.

If the SNP changes leader – putting Kate Forbes in place, or possibly Stephen Flynn if he can extricate himself from Westminster – the nationalists would be well placed to win the Scottish election of 2026.

Depending on the scale of any victory, the prospect of another independence referendum could be back in play.

Ahead of this year’s election, Scottish Labour’s best hope seems to be that the majority of those who back independence stay home.

But it, and everyone who wants Scotland to remain in the UK, needs to start working on the argument for why staying in the UK is Scotland’s best option.

Because my guess is that after 2026, that 50 per cent who back independence will be ready to come out and play.

Holyrood Newsletters

Holyrood provides comprehensive coverage of Scottish politics, offering award-winning reporting and analysis: Subscribe